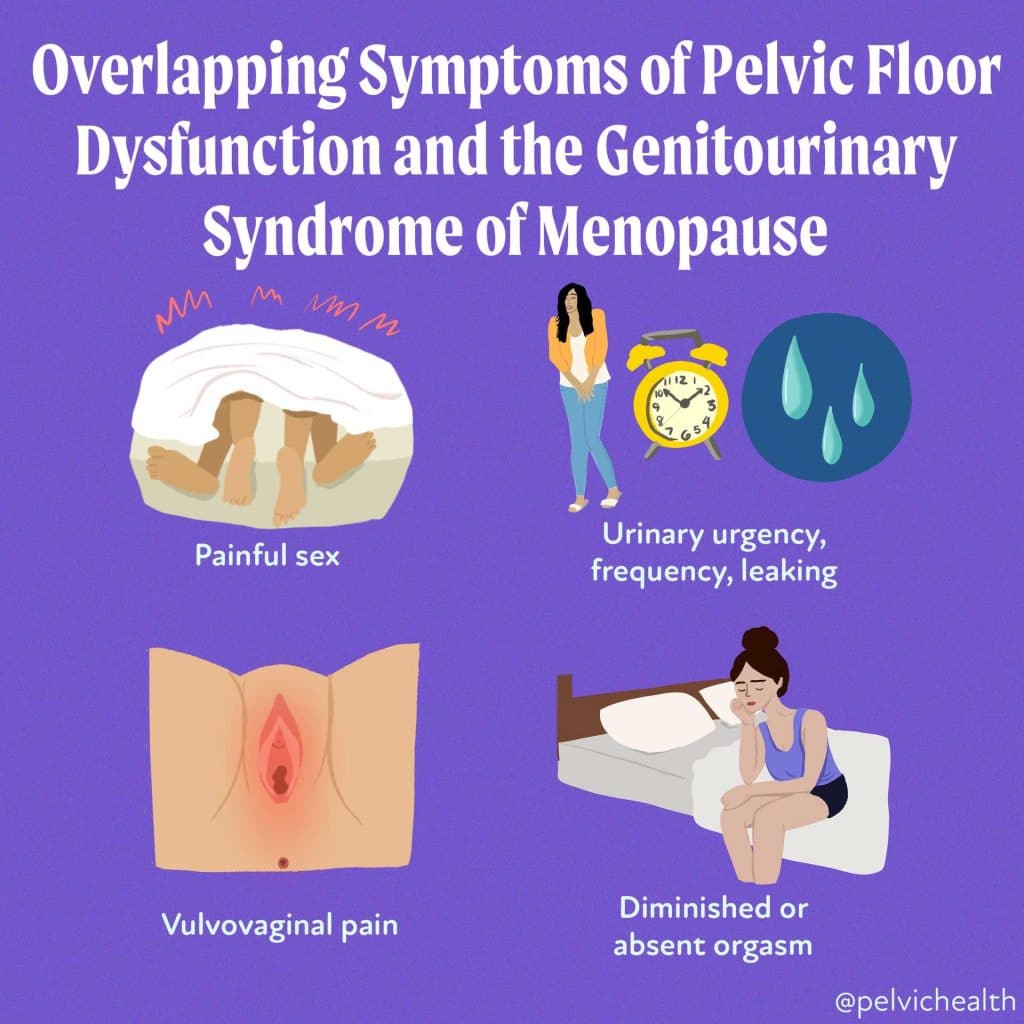

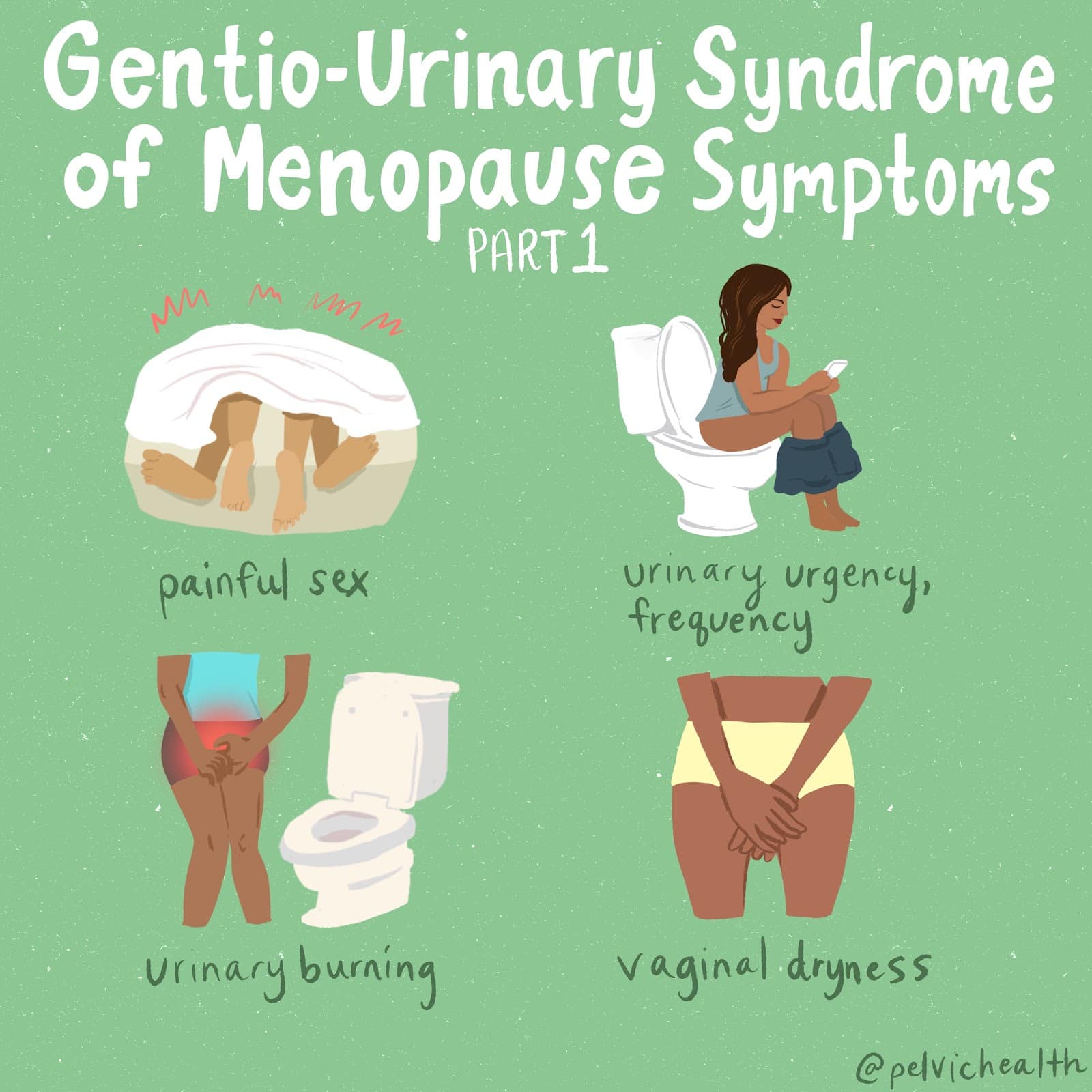

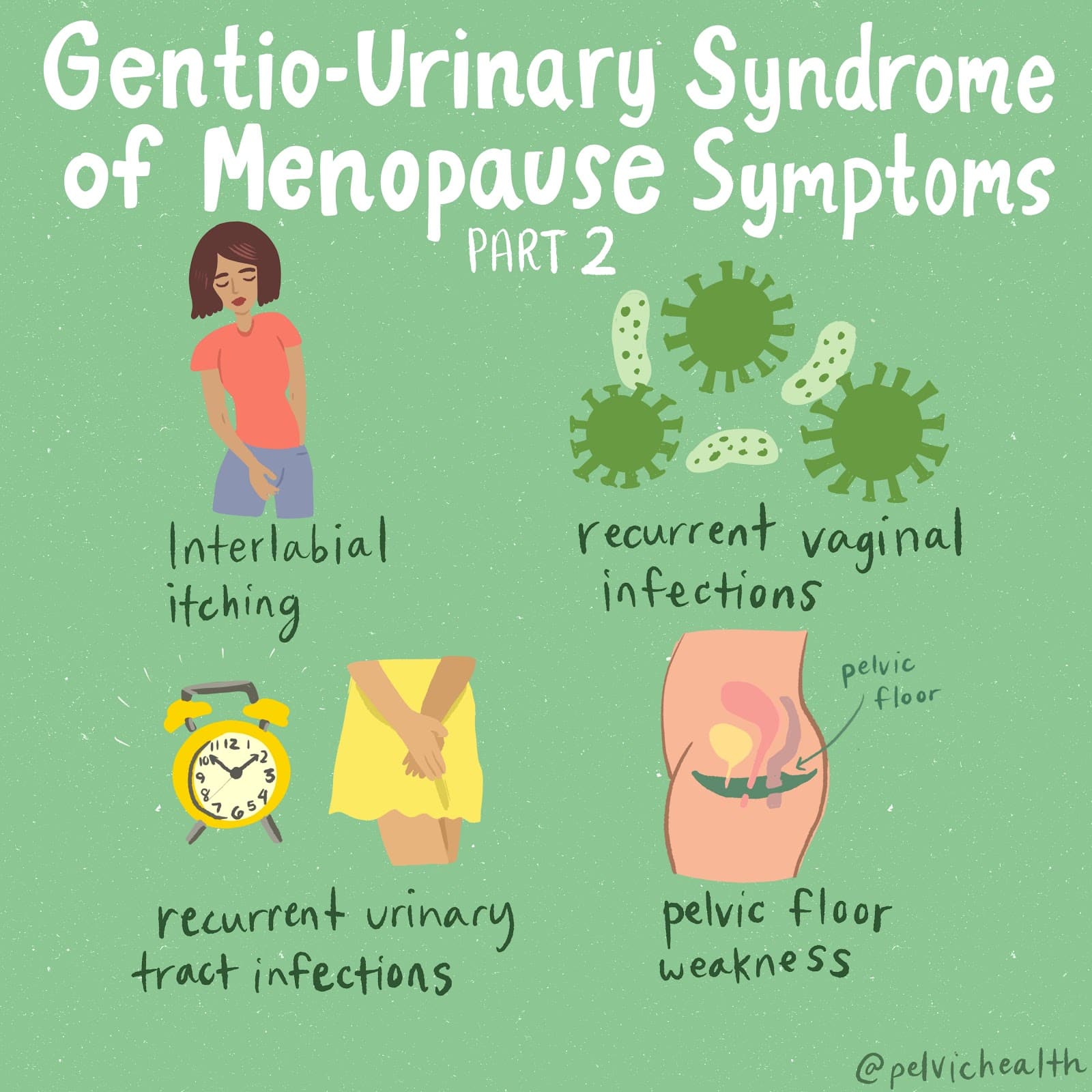

Menopause is more than just hot flushes, night sweats and mood changes! Even though 50% of the population goes through menopause the majority of people and healthcare providers are under-informed about menopause and safe and effective treatments. Too many people are suffering unnecessarily. Perimenopause, the precursor to menopause begins in the 40’s for most people and most women will be in menopause by their early 50’s. Beyond the systemic symptoms of menopause people will start to experience more subtle genitourinary symptoms that will continue to worsen over time if untreated. Painful sex, urinary urgency, frequency, leaking and burning, recurrent vaginal and urinary tract infections and vaginal dryness are symptoms of the Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM). The symptoms of GSM are also symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, which almost 50% of women suffer by the time they are in their 50s.

Systemic menopause symptoms are often treated with systemic hormonal therapy. This may not be sufficient for people developing GSM symptoms. The North American Menopause Society recommends vaginal estrogen for women in menopause to help counter GSM symptoms.

Menopause is more than just hot flushes, night sweats and mood changes! Even though 50% of the population goes through menopause the majority of people and healthcare providers are under-informed about menopause and safe and effective treatments. Too many people are suffering unnecessarily. Perimenopause, the precursor to menopause begins in the 40’s for most people and most women will be in menopause by their early 50’s. Beyond the systemic symptoms of menopause people will start to experience more subtle genitourinary symptoms that will continue to worsen over time if untreated. Painful sex, urinary urgency, frequency, leaking and burning, recurrent vaginal and urinary tract infections and vaginal dryness are symptoms of the Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM). The symptoms of GSM are also symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, which almost 50% of women suffer by the time they are in their 50s.

Systemic menopause symptoms are often treated with systemic hormonal therapy. This may not be sufficient for people developing GSM symptoms. The North American Menopause Society recommends vaginal estrogen for women in menopause to help counter GSM symptoms.

Differential Diagnosis:

GSM or Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction and GSM include:

- Urinary urgency, frequency, burning, nocturia

- Feelings of bladder or pelvic pressure

- Painful sex

- Diminished or absent orgasm

- Difficulty evacuating stool

- Vulvovaginal pain and burning

- Pain with sitting

An informed healthcare provider – whether a pelvic floor physical and occupational therapists or medical doctor – can do a vulvovaginal visual examination, a q-tip test to establish pain areas, and a digital manual examination to identify pelvic floor dysfunction, hormonal deficiencies, and pelvic organ prolapse. All women will experience GSM if enough time passes without appropriate medical management. The majority of people do not realize that menopausal women can benefit from a pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy examination to address the musculoskeletal factors that are also making them uncomfortable. The combination of pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy and medical management is key to help restore pleasurable sex and eliminate urinary and bowel concerns!

FACTS

From: https://www.letstalkmenopause.org/further-reading

- 6000 women enter menopause everyday

- 50 million women are currently menopausal in the US

- 84% of women struggle with genital, sexual and urinary discomfort that will not resolve on its own, and less than 25% seek help

- 80% of OBGYN residents admit to being ill-prepared to discuss menopause

- GSM is clinically detected in 90% of postmenopausal women, only ⅓ report symptoms when surveyed.

- Barriers to treatment: women often have to initiate the conversation, believe that the symptoms are just part of aging, women fail to link their symptoms with menopause.

- Only 13% of providers asked their patients about menopause symptoms.

- Even after diagnosis, the majority of women with GSM go untreated despite studies demonstrating a negative impact on quality of life. Hesitation to prescribe treatment by providers as well as patient-perceived concerns over safety profiles limit the use of topical vaginal therapies.

Hormone insufficiency can result in interlabial and vaginal itching. Other dermatologic issues such as Lichen Sclerosus and cutaneous yeast infections are just two of the many factors to also be considered.

Unfortunately people are vulnerable to recurrent vaginal and urinary tract infections in menopause due to:

- pH and tissue changes

- incomplete bladder emptying

- pelvic organ prolapse compromising urinary function

Recurrent infections are a leading cause of pelvic floor dysfunction! They must be stopped or the noxious visceral-somatic input can cause further pain and dysfunction after the infection is cleared. Furthermore, if the infections are left untreated without hormone therapy infections continue to occur and the consequences can be severe. Women can develop unprovoked pain, sex may be impossible, and undetected UTIs can lead to kidney problems and more sinister issues.

We encourage people to work with a menopause expert to monitor, prevent, and treat these issues as they are serious and treatable! We need to normalize the conversation about what happens during GSM, it is nothing to be embarrassed about and with the right care vulva owners can live their best lives! Pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy and medical management go hand in hand.

Treatment:

How We Can Help You

If you are having issues with your sexual function, it is in your best interest to get evaluated by a therapist for pelvic floor therapy, so they can establish what part, if any, of your pelvic floor may be contributing to the symptoms you are experiencing. During the course of the examination, the physical and occupational therapists will talk to you about your medical history and symptoms, including what you have been previously diagnosed with, the treatments or therapies you have had, and how effective or ineffective these therapies have been for you. It is significant to mention that we fully comprehend what you’ve been dealing with and that the majority of individuals are angry by the time they make it to see us. The physical and occupational therapists will conduct an evaluation of the patient’s nerves, muscles, joints, tissues, and movement patterns while doing the physical examination. After the examination is finished, your therapist will go over the results of the assessment with you. The physical and occupational therapists will conduct an evaluation to determine the cause of your symptoms and will establish both short-term and long-term therapy goals based on the results of the evaluation. Physical therapy treatments are typically administered between once and twice each week for a period of around 12 weeks. Your physical and occupational therapists will assist you in coordinating your recovery with all the other experts on your treatment team. They will provide you with an exercise regimen to complete at home and the sessions you attend in person. We are here to assist you in getting better and living the best life possible.

For more information about IC/PBS please check out our IC/PBS Resource List.

Treatment:

How We Can Help You

If you are having issues with your sexual function, it is in your best interest to get evaluated by a therapist for pelvic floor therapy, so they can establish what part, if any, of your pelvic floor may be contributing to the symptoms you are experiencing. During the course of the examination, the physical and occupational therapists will talk to you about your medical history and symptoms, including what you have been previously diagnosed with, the treatments or therapies you have had, and how effective or ineffective these therapies have been for you. It is significant to mention that we fully comprehend what you’ve been dealing with and that the majority of individuals are angry by the time they make it to see us. The physical and occupational therapists will conduct an evaluation of the patient’s nerves, muscles, joints, tissues, and movement patterns while doing the physical examination. After the examination is finished, your therapist will go over the results of the assessment with you. The physical and occupational therapists will conduct an evaluation to determine the cause of your symptoms and will establish both short-term and long-term therapy goals based on the results of the evaluation. Physical therapy treatments are typically administered between once and twice each week for a period of around 12 weeks. Your physical and occupational therapists will assist you in coordinating your recovery with all the other experts on your treatment team. They will provide you with an exercise regimen to complete at home and the sessions you attend in person. We are here to assist you in getting better and living the best life possible.

For more information about IC/PBS please check out our IC/PBS Resource List.

By Stephanie Prendergast, MPT, Cofounder, PHRC Los Angeles

Recently I was asked to write an article about pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy for the treatment of vulvodynia, which will be published later this year as a tool for gynecologists. Since our blog readers are a combination of clinicians and people with pelvic pain I figured I would share it here too. Warning: it is 15 pages and way beyond the length of a normal post! Happy reading!

Introduction of new nomenclature

In 2003, the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) defined vulvodynia as ‘vulvar discomfort, most often described as burning pain, occurring in the absence of relevant visible findings or a specific, clinically identifiable, neurological disorder’. This terminology served to acknowledge vulvar pain as a real disorder but fell short of classifying the syndrome as anything more than idiopathic pain. At that time, little was known about the pathophysiological mechanisms that cause vulvodynia and treatment options were limited. Over the past decade researchers have identified a number of causes of vulvodynia as well as associated factors/impairments. This resulted in the need to develop a new classification system to guide physicians towards better diagnosis and treatment. Last year the ISSVD, the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) and the International Pelvic Pain Society (IPPS) came together to review the evidence and publish the 2015 Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistent Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia. Individuals from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the National Vulvodynia Society also participated1.

The three societies reviewed the evidence and determined that persistent vulvar pain caused by a specific disorder can be categorized into seven different groups, with vulvodynia as a distinct separate entity of vulvar pain not caused by a specific disorder (Table 1). In addition, eight factors/impairments were shown to be associated with vulvodynia though the research does not yet support if these factors are a cause or an effect (Table 2). The final consensus and conclusion was that “vulvodynia is not one disease but a constellation of symptoms of several (sometimes overlapping) disease processes, which will benefit best from a range of treatments based on individual presentations”. While each case of vulvodynia is different, there is one underlying common component in these women that can cause significant pain and functional limitations: the pelvic floor muscles which are the focus of this article.

Table 1. 2015 Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistent Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia

A. Vulvar pain caused by a specific disorder*

a. Infectious (eg, recurrent candidiasis, herpes)

b. Inflammatory (eg, lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, immunobullous disorders)

c. Neoplastic (eg, Paget disease, squamous cell carcinoma)

d. Neurologic (eg, postherpatic neuralgia, nerve compression or nerve injury, neuroma)

e. Trauma (eg, female genital cutting, obstetrical)

f. Iatrogenic (eg, postoperative, chemotherapy, radiation)

g. Hormonal deficiencies (eg, genitourinary syndrome of menopause (vulvovaginal atrophy), lactational amenorrhea)

B. Vulvodynia – vulvar pain of at least 3 months’ duration, without a clear identifiable cause, which may have potential associated factors. The following are descriptors:

a. Localized (eg, vestibulodynia, clitorodynia) or generalized or mixed (localized and generalized)

b. Provoked (eg, insertional, contact) or spontaneous or mixed (provoked and spontaneous)

c. Onset (primary or secondary)

d. Temporal pattern (intermittent, persistent, constant, immediate, delayed)

*Women may have both a specific disorder (eg, lichen sclerosis) and vulvodynia

Table 2. 2015 Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistent Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia

Appendix: potential factors associated with vulvodynia*

- Comorbidities and other pain syndromes (eg, painful bladder syndrome, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, temporomandibular disorder)

- Genetics

- Hormonal factors ( eg, pharmacology induced)

- Inflammation

- Musculoskeletal (pelvic muscle overactivity, myofascial, biomechanical)

- Neurologic mechanisms – central and peripheral (neuroproliferation)

- Psychosocial factors (eg mood, interpersonal, coping, role, sexual function)

- Structural defects (eg, perineal descent)

*The factors are ranked in alphabetical order

Prevalence of musculoskeletal impairments in women with vulvodynia

When clinicians think of pelvic floor disorders, low-tone disorders associated with stress urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, the peripartum period and menopause often come to mind. The treatment solution is often ‘do your Kegels.’ Over the past two decades numerous, repeated studies have concluded that high-tone or hypertonic pelvic floor muscles are associated with pelvic pain disorders and dyspareunia, including vulvodynia2-5. While it may be less common to think of high-tone or overactive pelvic floor disorders, these disorders affect roughly 16% of women. Currently it is estimated that 10 million women have chronic pelvic pain5. Reissing et al reported that 90% of women diagnosed with provoked vestibulodynia demonstrated pelvic floor dysfunction6. In 2015 Witzeman et al conducted a proof of concept study to determine mucosal versus muscle pain sensitivity in women with provoked vestibulodynia. They concluded mucosal measures alone may not sufficiently capture the spectrum of the clinical pain report in woman with provoked vestibulodynia, which is consistent with the success of physical and occupational therapy in this population7. While it is not routine for a gynecology examination to include a screening of the pelvic floor muscles, tissues and nerves, a simple screening can be a useful tool and will be described in this article. Identifying musculoskeletal dysfunction will enable the gynecologist to determine if their patient is good candidate for pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy. Additionally, this article will describe the components of physical and occupational therapy evaluation and review the evidence for physical and occupational therapy treatment.

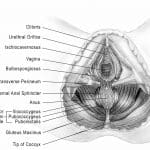

Pelvic Floor Anatomy and Physiology

The pelvic floor muscles are grouped as superficial or deep. The superficial muscles, also known as the urogenital diaphragm include the Bulbospongioisis, Ischiocavernosis, the Superficial Transverse Perineal muscles, and the urethral and anal sphincter muscles. These muscles, shown in Figure 1: Superficial muscles of the urogenital diaphragm9, are more commonly associated with vulvar pain syndromes6. The deep layer consists of the Levator Ani muscle group and the Coccygeus. Additionally, the Obturator Internus and Piriformis muscles play a role in pelvic floor muscle function. The pelvic floor has unique innervation and is never completely at rest, which helps us maintain continence but also comes with certain consequences in the face of dysfunction and treatment.

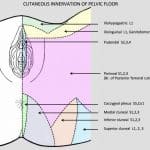

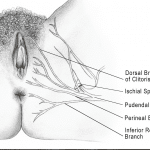

The pelvic floor muscles are innervated by sacral nerve roots, the pudendal nerve, and the levator ani nerve. There is slight controversy over specific innervation of the pelvic floor muscles, and naturally anatomic variance exists. For the sake of this article we will discuss the anatomy in a manner that is clinically relevant. The pudendal nerve arises from S2-4 nerve roots and is responsible for sensation for part of the vulva and vestibule, distal portion of the urethra and rectum, anal sphincter, perineum, vaginal mucosa, and pelvic floor muscles. It is a unique, mixed nerve with autonomic fibers in addition to its sensory and motor components. Pudendal neuralgia can be a cause and/or effect of pelvic floor dysfunction and vulvodynia and must be considered for an accurate differential diagnosis. Additionally, branches of the genitofemoral, ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric and posterior femoral cutaneous nerve can be sources of pelvic pain (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Peripheral Pelvic Nerve sensory distributions by Diane Jacobs in Dermoneuromodulation.

The muscles of the pelvic floor and their fascia are responsible for urinary , bowel, and sexual function as well as support of the pelvic viscera. When these muscles become hypertonic the symptoms that result are as numerous as their normal functions and manifest in a variety of combinations, (Table 3).

Table 3. Common symptoms of hypertonic pelvic floor muscles

- Urinary urgency, frequency, hesitancy, pain

- Constipation, difficulty and/or painful bowel movements

- Dyspareunia

- Pain with sitting

- Vulvar, perineal, anal and/or clitoral itching, pain or burning

- Anorgasmia or pain with orgasm

- Clothing and exercise intolerance

The pelvic floor muscles and nerves can become impaired in a number of ways, the first step to understanding how a patient developed pelvic pain is to begin with their history.

While we know pelvic floor dysfunction is associated with vulvodynia the pathophysiological processes are not fully understood. It is suspected that musculoskeletal dysfunction could arise via several different mechanisms, (Table 4).

Table 4. Possible causes of pelvic floor musculoskeletal dysfunction

- Higher muscle tension as a reflexive protective response to pain of different origins (neuropathic, infectious etc)

- Higher muscle tension in general (genetic predisposition)

- Volitional and/or subconscious pelvic floor guarding in response to stress and/or pain

- Biomechanical origins (labral tear, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, motor discoordination, overuse, repetitive strain, chronic constipation/straining/labor or compression injuries)

- Viscero-somatic reflex (gynecologic disease, IBS, vaginal or urinary tract infections)

- Inflammation of peripheral nerves

- Central nervous system hypersensitivity/overactivity

Patient History

As previously mentioned, multiple triggers of vulvodynia have been identified. The history is the perfect time to identify specific contributing factors to the development of vulvodynia for a symptomatic person. Table 4 lists the general categories of questions that are often included in a physical and occupational therapy evaluation. In addition to mechanistic questions, the physical and occupational therapy evaluation also includes a screening for central nervous system hypersensitivity/central sensitization. All pathophysiological factors, whether a trigger of vulvodynia or a consequence of it, need to be taken into account to formulate an individualized assessment and successful multimodal treatment plan.

Table 4. Evaluation Questions: General Categories

- General lifestyle and timing: When did your symptoms start and what do you think caused it? What makes it better and what makes it worse? Have you had pain from first vaginal insertion or did this develop over time? Location of this pain and other body pains?

- Urologic: Do you have a history of urinary tract infections? How many time in a day and at night do you void? Is it difficult to start your stream? Do you have pain before, during or after voiding and if so, where? How long do the symptoms last? Do you ever leak urine?

- Gynecologic: Do you have a history of vaginal infections? How many culture-proven infections have you had in the past year? History of other venereal or gynecologic diseases? Pregnancies, deliveries? Surgeries? Menstrual history and frequency? Oral contraceptive history?

- Gastrointestinal: Do you experience abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, hemorrhoids, fissures, or anal pain or itching?

- Sexual: Do you have pain with intercourse or arousal? Superficial or deep? Clitoral pain? Are you able to orgasm? Do you experience genital swelling with stimulation or bleeding or itching?

- Central Sensitization Screening

- Past Surgical and Medical History

Physical and Occupational Therapy Examination

The information gathered from the history will help guide the physical and occupational therapy examination. A primary focus of this article is the pelvic floor muscles, and this component of the physical and occupational therapy examination can be replicated by the general gynecologist. In addition to the pelvic floor examination, physical and occupational therapy evaluations also include other relevant external static and dynamic components to identify specific impairments. Table 5 lists common components of the external physical and occupational therapy examination while the next section describes the internal examination in more detail.

Table 5. External Physical and Occupational Therapy Physical Examination for Pelvic Pain

- Soft-tissue structures:

- Connective tissue evaluation of the abdomen, trunk, bony pelvis, legs

- Myofascial trigger point/hypertonus evaluation of the pelvic girdle muscles

- Neural Irritation/Dynamics testing ilioinguinal nerve, posterior femoral cutaneous, genitofemoral nerve, sciatic nerve

- Skeletal structures:

- Sacroiliac joints

- Hip joint

- Lumbar Spine

- Biomechanics/Motor Control evaluation

The external musculoskeletal system can cause as much havoc on the vulva as the pelvic floor muscles, tissue and nerves. Connective tissue restrictions can lead to local and referred pain, decreased blood flow, underlying muscle dysfunction, and tissue hypersensitivity10. Myofascial trigger points can also cause local and referred pain, proprioceptive dysfunction, and central sensitization11. The role and existence of myofascial trigger points are currently being debated in the medical community though numerous studies have suggested they play a significant role in pain syndromes. Neural irritation can stem from mechanical compromise including connective tissue and muscle dysfunction, it can be a cause of tissue and muscle dysfunction, and can independently cause pain anywhere in its distribution. Nerves can also be sensitized by repetitive infections or other metabolic processes. Research has also show a correlation between sacroiliac joint dysfunction, labral tears, and pelvic pain and therefore these areas also need to be screened12. The next component of the physical and occupational therapy is the skin inspection of the vulva and transvaginal examination, which will now be described with more detail.

Skin inspection and internal examination

- Skin inspection

- Vulva skin coloring, atrophic or dermatologic changes, fissures

- This is important to determine if the patient needs a referral to a vulvovaginal dermatologist and further work-up or treatment as described in other chapters

- Mobility of clitoral hood, size of clitoris

- The clitoris should be the size of the head of a q-tip, the clitoral hood should move easily, without pain, to expose the organ. Reduction in the size of the head of the clitoirs can be indicative of hormonal insuffiencies from oral contraceptive pill use, hormonal suppressive therapies, or menopause. Issues with mobility of the clitoral hood can stem from dermatologic diseases, infection, or connective tissue issues.

- Perineal movement with concentric contraction (squeeze) and Valsalva movement (push)

- Pelvic floor muscles of normal length should shorten with an attempted contraction and relax or ‘let go’ at a similar speed. If the muscles do not shorten it could be because they are already in a shortened position because of a contracture or because the patient lacks motor control. Impaired muscles show little movement, they may not relax after contracted or they may relax slowly.

- If no movement occurs during the Valsalva or push motion the patient may have impaired pelvic floor motor control. It is not common that muscles in a nulliparous woman with pain are at normal or ‘overlengthened’ positions, though this can occur in women with chronic constipation, vaginaly deliveries, and advanced age.

- Vestibule inspection and Q-tip test

- We inspect the vestibule for erythema and tissue integrity. The Q-tip test is done by lightly touching the vestibule and documenting location and severity of pain levels. This test is often painful for the patient and can sensitize them for the remainder of the examination. If you notice severe redness and they have unprovoked pain it may make sense to limit the number of areas touched or skip the Q-tip test because it is obvious they have pain.

- Reflex testing: anal wink, clitoral

- Vulva skin coloring, atrophic or dermatologic changes, fissures

- Internal pelvic floor muscle examination

- Note: If vestibule is erythemic and/or very painful on Q-tip test is is helpful to be cognizant of this area and avoid unnecessary pressure on this region while accessing the pelvic floor muscles and nerves. If it has already been observed that there is little movement during the requested voluntary movement and the vestibule is erythemic and/or very tender it is likely that a pelvic floor disorder is a component in your patient’s pain and a physical and occupational therapy evaluation is warranted. Therefore, it may be reasonable to stop the examination there. If you believe the patient can tolerate further examination the next steps can be performed to gather more information about the musculoskeletal system.

- General Considerations for the Pelvic Floor Examination

- During the digital internal examination, a single, gloved lubricated finger is used. The amount of pressure used is enough to whiten the nail bed when pressing on a table. For the sake of a gynecologic screening of pelvic floor muscles, the examiner is feeling for tone and elasticity while also asking for reports of tenderness and pain. Healthy muscles do not hurt when they are palpated. Repetitive palpation of numerous patients will afford the examiner the knowledge to be able to distinguish ‘tight’ from ‘normal’ by touch. Generally speaking ‘tight’ muscles are often painful and subjective reports from the patient can help guide interpretation of what the examiner is feeling. We are also examining for motor control. Can the patient contract the muscles? Are they already contacted in a state and unable to be volitionally relaxed? Is the patient able to Valsalva and move the pelvic floor into a lengthened position if they cannot volitionally relax the muscles? These are all factors to keep in mind as the examiner palpates the different pelvic floor muscles listed below. It may be easiest to use the right index finger when examining the muscles and nerves of the patient’s right pelvis and the left index finger when examining the left.

- Internal Pelvic Floor Palpation

- Obturator Internus and Tinel’s Sign for Pudendal Nerve Irritability

- The Obturator Internus is an external rotator of the hip. This makes it easy to identify by placing a finger in the vagina to a depth roughly just past the second knuckle at 3 or 9 o’clock on the patient’s left or right side, respectively, using the ventral aspect of a flat finger. The external hand can be placed on the patient’s outer knee, asking the patient to lightly press into your hand. When she moves in this manner the Obturator Internus will contract under your finger, confirming you are on the muscle. This muscle often causes pain at the ischial tuberosities and tailbone as well as contributes to generalized pelvic floor hypertonus. Importantly, the pudendal nerve travels through Alcock’s canal which is partially comprised of the aponeurosis of the Obturator Internus. This nerve can be examined for irritability by performing Tinel’s Sign. This is done by lightly palpating the nerve in the canal. This should feel like a ‘funny bone’ palpation in ‘normal’ cases, if light palpation causes sharp, shooting, stabbing pain or burning Tinel’s sign is considered to be positive in this location. If this test is positive the pudendal nerve can be a factor in the patient’s vestibulodynia and pelvic pain, see Figure 3: Pudendal Nerve branches9.

- Obturator Internus and Tinel’s Sign for Pudendal Nerve Irritability

-

-

- Urogenital Diaphragm

- The urogenital diaphragm contains the bulbospongiosus, ischiocavernosus, and superficial transverse perineum. Reissing et al found this superficial layer displayed considerable higher resting tone in patients with provoked veistibulodynia6. These muscles can be palpated using a pincer grasp by lightly using the index finger internally and the thumb of the same hand externally up and down the length of the bulbospongiosis, ischocavernosis, and superficial transverse perineum (Figure 1). These muscles can be activated by asking the patient to do a quick cough or quick flick muscle contraction. They are also involved in orgasm and are often tender and tight in women with painful or absent orgasm. These muscles are considered impaired if they are painful and/or cannot contract or relax.

- Levator Ani Muscle Group

- The Pubococcygeus can be found about 1 inch into the vagina between 7 and 11 o’clock on the right and 1 and 5 o’clock on the right. The puborectalis can be palpated going slightly deeper and straight down towards the table as it swings around the rectum, at 6 o’clock. The ischiococcygeus can be palpated by going slightly further into the vagina between 4 and 8 o’clock. The overall coordination of this muscle group can be tested by asking the patient to squeeze or do a kegel exercise. The muscles are considered impaired if palpation is painful, if they cannot contract, or if the muscles do not relax after a concentric contraction.

- Urogenital Diaphragm

-

A physical and occupational therapy internal examination also includes examination of the vulvar and peri-urethral connective tissue, palpation of all pudendal nerve branches, the coccygeus, and a more involved investigation of a patient’s motor control, muscle length, and strength and endurance. Impaired motor control, hypertonus, and tight/short muscles are often the cause of pelvic pain and dysfunction, physical and occupational therapy aims to normalize a patient’s specific impairments through various treatment techniques described later in this chapter.

Physical and Occupational Therapy Assessment and Treatment Plan

Following the history and the physical examination, a physical and occupational therapy assessment and treatment plan in formulated. During this segment of the evaluation the physical and occupational therapists will link the objective findings to specific symptoms and devise a treatment plan to normalize the impairments and to eliminate a patient’s symptoms. The physical and occupational therapists will also discuss short and long-term goals with the patient and create a rough timeline of what to expect. The treatment timeline will vary based on the severity, chronicity, and comorbidities a patient presents with. In an ideal world, physical and occupational therapy appointments occur 1-2 times per week for 1 hour for 8 -12 weeks initially. The constraints of managed care have forced treatment times and duration to often be shorter in many clinical settings than the syndrome requires, many patients choose to go to an out-of-network provider for longer treatment times and durations.

More often than not, women with vulvodynia have multiple pathophysiologic factors that led to development of their syndrome. It is critical for their doctors and physical and occupational therapists to formulate a differential diagnosis and collaborate on an interdisciplinary treatment plan. This point is best illustrated by case examples and a multimodal treatment algorithm.

Case Examples

- Leah is 30 years old. When she found a new sexual partner last year she developed multiple urinary tract infections that were appropriately treated with antibiotics but unfortunately led to several yeast infections. Upon evaluation she presented with high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction and her treatment plan included manual therapy and home exercises to loosen her tight muscles. Leah also consulted with a naturopathic doctor to get to the underlying cause of the repetitive infections. She developed candida in her gut as a result of long term and repetitive antibiotic use that led to vaginal yeast infections. These infections irritation her tissues and led to persisting muscle hypertonus which cause further pain. The musculoskeletal dysfunction, inflammation, and the systemic infections were primary causes of Leah’s vulvar pain. Her symptoms were successfully treated with manual physical and occupational therapy and a pelvic floor down-training home exercise program, a low-sugar and anti-candida diet, and a low-dose tricyclic antidepressant.

- Michelle is 30 years old. Her vulvo-vaginal pain developed after she was in a car accident. During the car accident her knees hit the dashboard, causing sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Because of the close relationship between the sacroiliac joint ligaments and the pudendal nerve, she subsequently developed pudendal nerve irritation which in turn caused a high-tone pelvic floor and constant vulvar burning. Because of the pudendal nerve irritation, Michelle could not initially tolerate physical and occupational therapy. She consulted with a pain management physician who prescribed Cymbalta and performed a pudendal nerve block (peripheral neuropathic treatment), then she resumed physical and occupational therapy. Her physical and occupational therapy treatment plan included manual therapy as well as orthopedic treatment strategies of joint mobilization and neuromuscular re-education for her sacroiliac joint ,which was a driving factor in Michelle’s case.

- Gwen is 49 and a triathlete. Her vulvar pain started two weeks after she started an exercise regime called Crossfit. She noticed the pain when she attempted to have intercourse. Upon examination, she did not have pelvic floor dysfunction or muscle tenderness which can be associated with changes in exercise regimes and injuries. Instead, her periods have been irregular and she is in peri-menopause. Upon inspection, her vulvar tissues were thin and atrophic. Her musculoskeletal structures were totally normal. The vulvar pain with intercourse coincided with a change in her exercise routine, but it also coincided with resuming intercourse after a period of inactivity and perimenopause. Her treatment consisted of topical hormonal cream and she did not need physical and occupational therapy.

- Michelle, who is 24 years old, always had painful periods and was prescribed oral contraceptives at the age of 16 to ease her painful periods. She had a boyfriend from the age of 19 -21 and was able to enjoy pleasurable intercourse. At the age of 21 she began using Accutane for skin issues. She was still taking oral contraceptives. Subsequently, she began to experience vulvar pain with tampon use, and for two years she experienced vulvar pain during sex that was becoming increasingly problematic. She then developed a Bartholin’s cyst that was surgically removed. Following this procedure, she felt daily pain unprovoked pain at the incision site. Upon physical examination she presented with scar tissue at the surgical incision site and also had other identified musculoskeletal findings that were likely contributed to her provoked pain. It is plausible that androgen insufficiency from oral contraceptives and Accutane was a contributing cause to the provoked vulvar pain that developed with insertion and that a neuroma secondary to surgery was contributing to the daily unprovoked pain. She was likely a poor surgical candidate because the hormonally sensitive vestibular tissue was compromised from her OCP and Accutane use. Her treatment involved cessation of the birth control pill, use of topical and systemic hormonal therapy, surgical excision of the neuroma, and physical and occupational therapy. Her case was hormonal, genetic, peripheral neuropathic, and musculoskeletal.

- Barb is 53 and the mother of two children, ages 25 and 27, delivered vaginally. She underwent a complete hysterectomy and anterior vaginal wall repair for uterine and bladder prolapse. Mesh was used in this repair. Following surgery, Barb developed severe and debilitating vulvar pain. Her pain was caused by peripheral nerve irritation from the mesh and it eventually was removed. Following the removal of the mesh she underwent pharmacologic therapy for CNS hypersensitivity, pudendal nerve blocks, and physical and occupational therapy, which resulted in resolution of her symptoms.

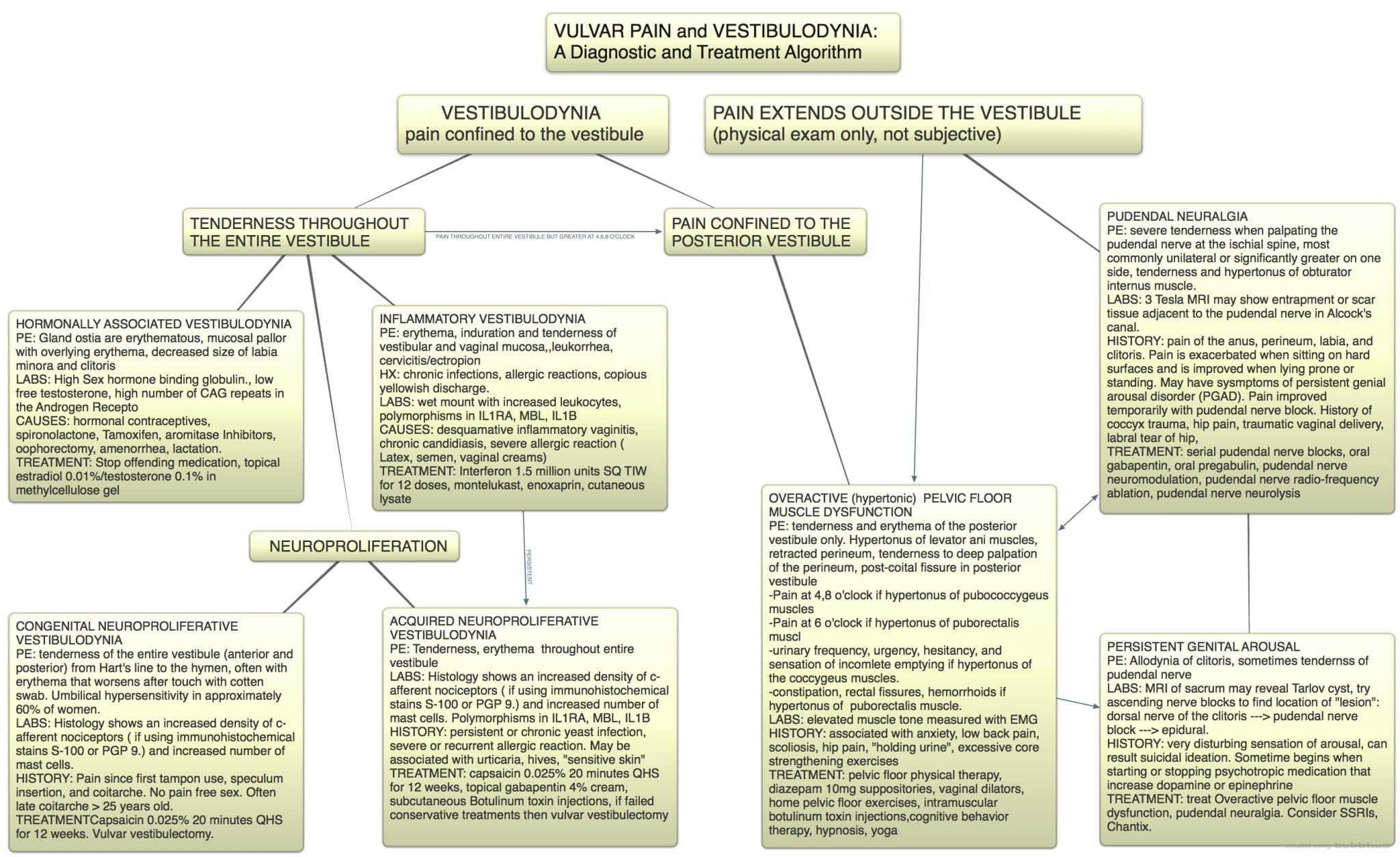

Assessment and Treatment

As shown in the case examples, it is common for patients with similar symptoms to require complete different treatment plans. In order to effective devise an initial treatment, a differential diagnosis and assessment is required. These principles are best highlighted with an interdisciplinary treatment algorithm, see Figure 4: Vulvar pain and vesitibulodynia, a diagnostic and treatment algorithm13.

Figure 4. Vulvar pain diagnosis and treatment algorithm by Andrew Goldstein.

Physical therapists are well-positioned to serve as a ‘case manager’ for patients due to the length of time and repetitive visits over time that they are afforded with the patient. It is important that a treatment plan is well-coordinated with all of the treating doctors and providers as patients often initially fail or do not tolerate needed treatments. Success lies in the ability to troubleshoot though treatment plan hiccups and find a plan that is tolerated and effective.

In addition to the case management role, the physical and occupational therapy treatment plan consists of various combinations of treatment strategies listed in Table 6.

Table 6. Physical and Occupational Therapy Treatment Options

- Manual Therapy Techniques

- Connective Tissue Manipulation

- Myofascial release and myofascial trigger point release

- Neural mobilizations

- Joint mobilizations

- Pelvic Floor and Girdle Neuromuscular Re-education

- Pain physiology education

- Behavioral and lifestyle modifications to reduce fear/avoidance and catastrophization

- Peripheral and central nervous system desensitization strategies

- Home exercise program development to supplement in-office treatments

- Foam rolling

- Pelvic floor muscle relaxation exercises (Pelvic Floor Drop)

- Stretching when appropriate, strengthening if weak

Evidence for Physical and Occupational Therapy Treatment

Physical therapy treatment for vulvodynia is recommended by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology14. Due to the heterogenity of the syndrome and the multitude of physical and occupational therapy treatment options the literature often addresses combination approaches to treatment vs individual techniques. This article will highlight a few diverse studies.

In 2009, FitzGerald et al published a randomized feasibility trial of 2 methods of manual therapy in patients with chronic pelvic pain. 48 subjects were recruited and randomized to receive either skilled, myofascial physical and occupational therapy or global Swedish massage. Each group received 10 weekly 1-hour treatments. Therapist adherence to the treatment protocols was excellent. The global response assessment rate was 57% in the myofascial physical and occupational therapy group was significantly higher than the rate of 21% in the global therapeutic massage treatment group (P=.03)15.

In another study, Gentilcore-Saulnier et al determined that women with provoked vesitbulodynia had higher tonic sEMG activity in their superficial pelvic floor muscles compared with a control group and a heightened response to painful stimuli when these muscles were subjected to pressure. Physical therapy treatment resulted in less pelvic floor muscle responsiveness to pain, less pelvic floor muscle tone, improved vaginal flexibility and improved pelvic floor muscle capacity16.

In a multimodal study, Goldfinger et al compared the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy and physical and occupational therapy on pain and psychosocial outcomes in women with provoked vestibulodynia. 20 women were randomized to receive CBT or PT. Both treatment groups demonstrated significant decreases in vulvar pain during sexual intercourse, with 70% and 80% of the women demonstrating a moderate clinically important decrease in pain (>30%) after treatment17.

Conclusion

Vulvar pain affects up to 20% of women at some point in their lives and the majority of women with vulvar pain have associated pelvic floor impairments. It is suggested that these impairments are a cause of vulvodynia in some cases, whereas in other cases, they may be an effect. A quick screening of the pelvic floor muscles can be performed in the gynecology office and should be utilized when a patient reports symptoms of pelvic pain. Because of the heterogenity of the syndrome, successful treatment plans are multimodal and include physical and occupational therapy.

How to find a pelvic floor physical and occupational therapists

Pelvic floor physical and occupational therapistss can be found through the American Physical and Occupational Therapy Association’ Section on Women’s Health or through the International Pelvic Pain Society’s website.

References

- Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS consensus terminology and classification of persistent Vulvar pain and Vulvodynia. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2016;13(4):607–612. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.167.

- Lev-Sagie A, Witkin SS. Recent advances in understanding provoked vestibulodynia. F1000Research. 2016;5:2581. doi:10.12688/f1000research.9603.1. (M/S and V)

- Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Brown C, Bergeron S, Stein A, Kellogg-Spadt S. Vulvodynia: Assessment and treatment. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2016;13(4):572–590. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.020.

- Thibault-Gagnon S, Morin M. Active and passive components of pelvic floor muscle tone in women with provoked Vestibulodynia: A perspective based on a review of the literature. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2015;12(11):2178–2189. doi:10.1111/jsm.13028.

- Gyang A, Hartman M, Lamvu G. Musculoskeletal causes of chronic pelvic pain. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;121(3):645–650. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e318283ffea.

- Reissing E, Brown C, Lord M, Binik Y, Khalifé S. Pelvic floor muscle functioning in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2005;26(2):107–113. doi:10.1080/01443610400023106.

- Witzeman K, Nguyen RHN, Eanes A, As-Sanie S, Zolnoun D. Mucosal versus muscle pain sensitivity in provoked vestibulodynia. Journal of Pain Research. August 2015:549. doi:10.2147/jpr.s85705.

- Jacobs, D. Dermo Neuro Modulating: Manual Treatment for Peripheral Nerves and Especially Cutaneous Nerves. Diane Jacobs; 2016.

- Rummer EH, Prendergast SA. Pelvic Pain Explained: What everyone needs to know. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2016. https://www.abebooks.com/9781442248311/Pelvic-Pain-Explained-What-Needs-1442248319/plp. Accessed January 25, 2017.

- FitzGerald MP, Kotarinos R. Rehabilitation of the short pelvic floor. I: Background and patient evaluation. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2003;14(4):261–268. doi:10.1007/s00192-003-1049-0.

- Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial pain and dysfunction: The trigger point manual: Volume 2: Lower extremities. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; January 1, 1992.

- Hartmann D, Strauhal MJ, Nelson CA. Treatment of women in the United States with localized, provoked Vulvodynia. Journal of Women’s Health Physical and Occupational Therapy. 2007;31(3):34–38. doi:10.1097/01274882-200731030-00005.

- King M, Rubin R, Goldstein AT. Current uses of surgery in the treatment of genital pain. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2014;6(4):252–258. doi:10.1007/s11930-014-0032-8.

- Committee opinion no 673 summary. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2016;128(3):676–677. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000001639.

- FitzGerald MP, Anderson RU, Potts J, et al. Randomized Multicenter feasibility trial of Myofascial physical and occupational therapy for the treatment of Urological chronic pelvic pain Syndromes. The Journal of Urology. 2013;189(1):S75–S85. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.018.

- Gentilcore-Saulnier E, McLean L, Goldfinger C, Pukall CF, Chamberlain S. Pelvic floor muscle assessment outcomes in women with and without provoked Vestibulodynia and the impact of a physical and occupational therapy program. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(2):1003–1022. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01642.x.

- Goldfinger C, Pukall CF, Thibault-Gagnon S, McLean L, Chamberlain S. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy and physical and occupational therapy for provoked Vestibulodynia: A Randomized pilot study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2016;13(1):88–94. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.003.

FAQ

What are pelvic floor muscles?

The pelvic floor muscles are a group of muscles that run from the coccyx to the pubic bone. They are part of the core, helping to support our entire body as well as providing support for the bowel, bladder and uterus. These muscles help us maintain bowel and bladder control and are involved in sexual pleasure and orgasm. The technical name of the pelvic floor muscles is the Levator Ani muscle group. The pudendal nerve, the levator ani nerve, and branches from the S2 – S4 nerve roots innervate the pelvic floor muscles. They are under voluntary and autonomic control, which is a unique feature only they possess compared to other muscle groups.

What is pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy?

Pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy is a specialized area of physical and occupational therapy. Currently, physical and occupational therapistss need advanced post-graduate education to be able to help people with pelvic floor dysfunction because pelvic floor disorders are not yet being taught in standard physical and occupational therapy curricula. The Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Center provides extensive training for our staff because we recognize the limitations of physical and occupational therapy education in this unique area.

What happens at pelvic floor therapy?

During an evaluation for pelvic floor dysfunction the physical and occupational therapists will take a detailed history. Following the history the physical and occupational therapists will leave the room to allow the patient to change and drape themselves. The physical and occupational therapists will return to the room and using gloved hands will perform an external and internal manual assessment of the pelvic floor and girdle muscles. The physical and occupational therapists will once again leave the room and allow the patient to dress. Following the manual examination there may also be an examination of strength, motor control, and overall biomechanics and neuromuscular control. The physical and occupational therapists will then communicate the findings to the patient and together with their patient they establish an assessment, short term and long term goals and a treatment plan. Typically people with pelvic floor dysfunction are seen one time per week for one hour for varying amounts of time based on the severity and chronicity of the disease. A home exercise program will be established and the physical and occupational therapists will help coordinate other providers on the treatment team. Typically patients are seen for 3 months to a year.

What is pudendal neuralgia and how is it treated?

Pudendal Neuralgia is a clinical diagnosis that means pain in the sensory distribution of the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve is a mixed nerve that exits the S2 – S4 sacral nerve roots, we have a right and left pudendal nerve and each side has three main trunks: the dorsal branch, the perineal branch, and the inferior rectal branch. The branches supply sensation to the clitoris/penis, labia/scrotum, perineum, anus, the distal ⅓ of the urethra and rectum, and the vulva and vestibule. The nerve branches also control the pelvic floor muscles. The pudendal nerve follows a tortuous path through the pelvic floor and girdle, leaving it vulnerable to compression and tension injuries at various points along its path.

Pudendal Neuralgia occurs when the nerve is unable to slide, glide and move normally and as a result, people experience pain in some or all of the above-mentioned areas. Pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy plays a crucial role in identifying the mechanical impairments that are affecting the nerve. The physical and occupational therapy treatment plan is designed to restore normal neural function. Patients with pudendal neuralgia require pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy and may also benefit from medical management that includes pharmaceuticals and procedures such as pudendal nerve blocks or botox injections.

What is interstitial cystitis and how is it treated?

Interstitial Cystitis is a clinical diagnosis characterized by irritative bladder symptoms such as urinary urgency, frequency, and hesitancy in the absence of infection. Research has shown the majority of patients who meet the clinical definition have pelvic floor dysfunction and myalgia. Therefore, the American Urologic Association recommends pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy as first-line treatment for Interstitial Cystitis. Patients will benefit from pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy and may also benefit from pharmacologic management or medical procedures such as bladder instillations.

Who is the Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Team?

The Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Center was founded by Elizabeth Akincilar and Stephanie Prendergast in 2006, they have been treating people with pelvic floor disorders since 2001. They were trained and mentored by a medical doctor and quickly became experts in treating pelvic floor disorders. They began creating courses and sharing their knowledge around the world. They expanded to 11 locations in the United States and developed a residency style training program for their employees with ongoing weekly mentoring. The physical and occupational therapistss who work at PHRC have undergone more training than the majority of pelvic floor physical and occupational therapistss and as a result offer efficient and high quality care.

How many years of experience do we have?

Stephanie and Liz have 24 years of experience and help each and every team member become an expert in the field through their training and mentoring program.

Why PHRC versus anyone else?

PHRC is unique because of the specific focus on pelvic floor disorders and the leadership at our company. We are constantly lecturing, teaching, and staying ahead of the curve with our connections to medical experts and emerging experts. As a result, we are able to efficiently and effectively help our patients restore their pelvic health.

Do we treat men for pelvic floor therapy?

The Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Center is unique in that the Cofounders have always treated people of all genders and therefore have trained the team members and staff the same way. Many pelvic floor physical and occupational therapistss focus solely on people with vulvas, this is not the case here.

Do I need pelvic floor therapy forever?

The majority of people with pelvic floor dysfunction will undergo pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy for a set amount of time based on their goals. Every 6 -8 weeks goals will be re-established based on the physical improvements and remaining physical impairments. Most patients will achieve their goals in 3 – 6 months. If there are complicating medical or untreated comorbidities some patients will be in therapy longer.

By Stephanie Prendergast and Elizabeth Akincilar-Rummer

Tony is one of those people who seem superhuman. In his early 30s, he’s lean and athletic. When he isn’t chasing after one of his three young children or helping to run a successful family business, you can find him surfing, hunting, snowboarding, golfing, swimming, or playing basketball.

It’s hard to believe that at one time, this guy who has such a passion for living was all but convinced that his life was over. But there was a time, not all that long ago, when he was sure that he’d never participate in another sport that he loved, let alone be able to work or even have relations with his wife.

It was on an unseasonably warm afternoon in February back in 2003 when Tony’s full and happy life took an unexpected detour. On that day, as usual, he was in active mode, attempting to pull off the perfect handstand when all of a sudden, he felt a sharp pinching pain in his lower abs.

Three doctors later, he was diagnosed with an “abdominal strain” and prescribed core-strengthening exercises. The exercises made his pain worse, and in a matter of weeks his symptoms exploded. The sharp pain in his abs snowballed into pain with sitting, constant perineum and groin pain, and a burning pain at the tip of his penis.

Unable to find any answers from the doctors he visited, he turned to the Internet. That’s when the fear and panic set in. After spending hours online, he discovered that his symptoms were a match with a disorder called “pudendal nerve entrapment”or “PNE.”

After reading a litany of stories about PNE, he was convinced that he needed surgery as soon as possible to free his entrapped pudendal nerve. Otherwise, according to the information he was uncovering, his symptoms would continue to worsen. He even contacted one of the doctors mentioned in the online forums who performed the surgery. The doctor encouraged him to fly out and schedule the surgery with him right away.

“I was terrified,” he recalls, “I was reading all of these horror stories, and I believed that if I didn’t get surgery as soon as possible, I would end up impotent and incontinent. Even with surgery I was afraid of what my life was going to become.”

However, before he signed up for surgery, he decided to see one more doctor in San Francisco. Thankfully, that doctor was one of the few in the country in the know about male pelvic pain. The doctor explained that trigger points and muscle spasms in the pelvic floor—and in Tony’s case, in the abdomen—have the potential to cause all of the symptoms he was experiencing. The doctor then prescribed pelvic floor PT to treat his pain. Finally, he was getting what seemed like a reliable explanation for what was happening to him. Plus, there was a treatment option available that was much more conservative than going under the knife.

“I admit at first I didn’t believe PT was going to help me,” he says. “But I decided I would just do it as a final effort before I got the surgery.”

After the first session with Stephanie, Tony felt a slight bit of relief. Ultimately, with regular PT sessions—at first twice weekly and then weekly—his pain and symptoms began to diminish, until eventually they were gone altogether.

“Today I have zero pain,” he says. “But it didn’t go away overnight,” he is quick to add. “It took time, patience, and a lot of commitment. And there were times during my sessions with Steph when I would break down because I was still so anxious about all that I had read on the Internet.”

Tony began PT with Stephanie in January of 2004, and by January of 2006, he was completely symptom-free. Today he is living an unrestricted, active life without pain.

Unfortunately, Tony’s struggle with pelvic pain is all too common. Research shows that between 8% and 10% of the male population suffers from pelvic pain. But that number is likely higher because studies also show that 50% of men will deal with prostatitis at some point in their lives, and pelvic pain in men is consistently misdiagnosed as prostatitis.

Tony’s ordeal is also common in that, because he couldn’t get answers from his doctors, he turned to the Internet for information, a move that led him down a dark road of misinformation. The reality is that men with pelvic pain have an even harder time getting a proper diagnosis and treatment than women with pelvic pain.

For one thing, the medical community systematically misdiagnosis any pelvic pain symptom in men, —whether perineal pain, post-ejaculatory pain, urinary frequency, or penile pain—as a prostatitis infection, despite the absence of virus or bacteria.

The absence of a virus or bacteria simply means a switch in diagnosis from “prostatitis infection” to “chronic nonbacterial prostatitis.” Typically, from there the doctor writes out an Rx for a few months worth of antibiotics and the drug Flomax, and the patient is sent on his way.

In the beginning, because antibiotics have an analgesic effect, patients will actually feel a tiny bit better. But before long the effect wears off, and they’re right back where they started; in pain with no relief.

What’s so maddening about this misdiagnosis loop is that in 1995, the National Institute of Health (NIH) clearly stated that the term “chronic nonbacterial prostatitis” does not explain nor is even related to the symptoms these men suffer. To describe the symptoms they actually do suffer with, the NIH adopted the term: “chronic pelvic pain syndrome.”

The symptoms the NIH listed as being those of pelvic pain are: painful urination, hesitancy, frequency, penile, scrotal, rectal, and perineal pain, as well as bowel and sexual dysfunction. (In addition, in male pelvic pain patients, it’s common for them to feel as though they have a golf ball or tennis ball in their perineum.)

Despite the NIH’s edict, and more than 15 years later, men with pelvic pain are still getting that diagnosis to nowhere: “chronic nonbacterial prostatitis.”

Just ask Derrick.

A successful CFO, and an upbeat family man, Derrick is happily married with three children. It was in early 2002 that he began experiencing perineal pain, post-ejaculatory pain, and pain with sitting.

For nearly three years he was left to flounder in the misdiagnosis loop of chronic nonbacterial prostatitis. During that time, he endured several painful and misdirected tests and procedures at his urologist’s office. At one point, he even believed he had cancer.

“I was pretty frustrated and it was psychologically pretty challenging,” he says. “I was in my early 30s, but I felt very old. It impacted my sex life and all of my relationships.”

Because of the effect it was having on his life, Derrick sought help from a psychiatrist. It was his psychiatrist who referred him to a doctor in San Francisco who diagnosed him with pelvic pain and sent him to Liz for physical and occupational therapy.

“PT has been the only thing that has helped my pain and discomfort,” he says. “Now it’s something that I must manage through therapy every two to three months, but I’m okay with that.”

As both Tony and Derrick discovered, the right PT is the best treatment for men suffering with pelvic pain.

For the most part, there are four rungs to the ladder of pelvic pain treatment whether for a man or a woman. They are: working out external trigger points, working out internal trigger points and lengthening tight muscles, connective tissue manipulation, and correcting structural abnormalities.

For male patients, the internal trigger point release and muscle lengthening (internal work) is done via the anus because this is how the PT can gain access to the pelvic floor muscles. (Click here to read more about the right PT for pelvic pain.)

Despite the proven fact that PT is the best treatment for pelvic pain in men, it’s often difficult for men to get into the door of a pelvic pain PT clinic. That’s because not all pelvic floor PTs treat men. This is the second major reason men have an even harder time than women getting on the road to recovery from pelvic pain.

Today, the majority of pelvic floor PTs are women. And, many of these women are uncomfortable treating the opposite sex. For some female PTs, it simply boils down to them not being comfortable dealing with the penis and testicles. Among their qualms: What if the patient gets an erection? How do I deal with that?

Coming from a practice where 15% to 20% of our patients are men with pelvic pain, here’s our advice. If a male patient does get an erection, address it with a simple: “Don’t worry, it happens.” And move on. The bottom line is if you’re in the medical profession, you shouldn’t be intimidated by human anatomy. If you’re afraid to fly, don’t become a pilot. If you hate the water, don’t join the Navy. If you’re a vegan, don’t become a butcher. You get the picture!

Pelvic pain does not discriminate between sexes, and neither should those who treat it. Unfortunately even prominent organizations qualify pelvic pain as a “women’s health” issue. This needs to change.

To be fair, for some female PTs, their discomfort stems from the fact that they have received little to no formal education on how to treat the male pelvic floor. Frustratingly, there is very little education available to PTs on treating the pelvic floor in general. And what education is available is typically focused on the practical treatment of the female pelvic floor. For instance, when PTs take a class they practice on other PTs. So female PTs practice on other women, and when they return to their clinics, they’re not confident treating the male pelvic floor. While this is more understandable than simply not treating male patients because of a social discomfort, it’s still not acceptable.

The good news is that, in general, men are actually less complicated to treat than women. For one thing, there is no vestibule to deal with. The vestibule is an organ that’s full of nerves with the potential to become angry. In addition, the male pelvic floor doesn’t have mucosa that’s exposed to outside bacteria or other agents; therefore, men aren’t as vulnerable as women to UTIs and yeast infections, which can exacerbate the pain cycle. Lastly, male patients aren’t dealing with the large fluctuations in hormones that female patients deal with.

Conversely, what male patients and female patients do have in common is that with the male pelvic floor, as with the female pelvic floor, musculoskeletal impairments such as hypertonic muscles, connective tissue restrictions, pudendal nerve irritation, and myofascial trigger points commonly cause the symptoms of pelvic pain in men.

Another commonality is that lifestyle issues contribute to male pelvic pain just as they do to female pelvic pain. For instance, in Tony’s case, his activities that might have contributed to his pain included a history of doing upwards of 200 sit ups a day, and his regular long bike rides. Plus, at a young age he was told to “pucker” or hold his pelvic floor in order to avoid getting hemorrhoids.

As for Derrick, not only did he sit for long hours every day at a desk, he also had a long commute to and from work.

“In addition to solving my pain issues, PT helped me understand how my problems might have started to begin with, and it taught me to avoid certain potential triggers,” says Tony, who no longer rides a bike, does sit ups, or holds his pelvic floor. In addition, he has set up a standing work station to give him the option of not sitting at work.

For his part, Derrick has cut back on his sitting, and when he does have to sit, he takes frequent breaks to stand up and move around.

Both men are thankful they were put on the right path to pelvic floor PT, and both men have the same resounding advice for other men who are suffering from pelvic pain and are looking for relief. “Try pelvic pain PT!” they both advise. “PT saved my life,” adds Tony.

What Pelvic Pain!? : Click here to read a detailed account of how PT got Tony better.

Now we want to hear from you!

If you are a man with pelvic pain, please share your experiences with us.

All our very best,

Stephanie and Liz

FAQ

What are pelvic floor muscles?

The pelvic floor muscles are a group of muscles that run from the coccyx to the pubic bone. They are part of the core, helping to support our entire body as well as providing support for the bowel, bladder and uterus. These muscles help us maintain bowel and bladder control and are involved in sexual pleasure and orgasm. The technical name of the pelvic floor muscles is the Levator Ani muscle group. The pudendal nerve, the levator ani nerve, and branches from the S2 – S4 nerve roots innervate the pelvic floor muscles. They are under voluntary and autonomic control, which is a unique feature only they possess compared to other muscle groups.

What is pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy?

Pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy is a specialized area of physical and occupational therapy. Currently, physical and occupational therapistss need advanced post-graduate education to be able to help people with pelvic floor dysfunction because pelvic floor disorders are not yet being taught in standard physical and occupational therapy curricula. The Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Center provides extensive training for our staff because we recognize the limitations of physical and occupational therapy education in this unique area.

What happens at pelvic floor therapy?

During an evaluation for pelvic floor dysfunction the physical and occupational therapists will take a detailed history. Following the history the physical and occupational therapists will leave the room to allow the patient to change and drape themselves. The physical and occupational therapists will return to the room and using gloved hands will perform an external and internal manual assessment of the pelvic floor and girdle muscles. The physical and occupational therapists will once again leave the room and allow the patient to dress. Following the manual examination there may also be an examination of strength, motor control, and overall biomechanics and neuromuscular control. The physical and occupational therapists will then communicate the findings to the patient and together with their patient they establish an assessment, short term and long term goals and a treatment plan. Typically people with pelvic floor dysfunction are seen one time per week for one hour for varying amounts of time based on the severity and chronicity of the disease. A home exercise program will be established and the physical and occupational therapists will help coordinate other providers on the treatment team. Typically patients are seen for 3 months to a year.

What is pudendal neuralgia and how is it treated?

Pudendal Neuralgia is a clinical diagnosis that means pain in the sensory distribution of the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve is a mixed nerve that exits the S2 – S4 sacral nerve roots, we have a right and left pudendal nerve and each side has three main trunks: the dorsal branch, the perineal branch, and the inferior rectal branch. The branches supply sensation to the clitoris/penis, labia/scrotum, perineum, anus, the distal ⅓ of the urethra and rectum, and the vulva and vestibule. The nerve branches also control the pelvic floor muscles. The pudendal nerve follows a tortuous path through the pelvic floor and girdle, leaving it vulnerable to compression and tension injuries at various points along its path.

Pudendal Neuralgia occurs when the nerve is unable to slide, glide and move normally and as a result, people experience pain in some or all of the above-mentioned areas. Pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy plays a crucial role in identifying the mechanical impairments that are affecting the nerve. The physical and occupational therapy treatment plan is designed to restore normal neural function. Patients with pudendal neuralgia require pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy and may also benefit from medical management that includes pharmaceuticals and procedures such as pudendal nerve blocks or botox injections.

What is interstitial cystitis and how is it treated?

Interstitial Cystitis is a clinical diagnosis characterized by irritative bladder symptoms such as urinary urgency, frequency, and hesitancy in the absence of infection. Research has shown the majority of patients who meet the clinical definition have pelvic floor dysfunction and myalgia. Therefore, the American Urologic Association recommends pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy as first-line treatment for Interstitial Cystitis. Patients will benefit from pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy and may also benefit from pharmacologic management or medical procedures such as bladder instillations.

Who is the Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Team?

The Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Center was founded by Elizabeth Akincilar and Stephanie Prendergast in 2006, they have been treating people with pelvic floor disorders since 2001. They were trained and mentored by a medical doctor and quickly became experts in treating pelvic floor disorders. They began creating courses and sharing their knowledge around the world. They expanded to 11 locations in the United States and developed a residency style training program for their employees with ongoing weekly mentoring. The physical and occupational therapistss who work at PHRC have undergone more training than the majority of pelvic floor physical and occupational therapistss and as a result offer efficient and high quality care.

How many years of experience do we have?

Stephanie and Liz have 24 years of experience and help each and every team member become an expert in the field through their training and mentoring program.

Why PHRC versus anyone else?

PHRC is unique because of the specific focus on pelvic floor disorders and the leadership at our company. We are constantly lecturing, teaching, and staying ahead of the curve with our connections to medical experts and emerging experts. As a result, we are able to efficiently and effectively help our patients restore their pelvic health.

Do we treat men for pelvic floor therapy?

The Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Center is unique in that the Cofounders have always treated people of all genders and therefore have trained the team members and staff the same way. Many pelvic floor physical and occupational therapistss focus solely on people with vulvas, this is not the case here.

Do I need pelvic floor therapy forever?

The majority of people with pelvic floor dysfunction will undergo pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy for a set amount of time based on their goals. Every 6 -8 weeks goals will be re-established based on the physical improvements and remaining physical impairments. Most patients will achieve their goals in 3 – 6 months. If there are complicating medical or untreated comorbidities some patients will be in therapy longer.

By Admin

Art imitates life, though Hollywood’s imitation of sex is often a crude copy. Now, don’t get me wrong, I do enjoy a good rom-com, and I may or may not be on my second viewing of True Blood, but sometimes I just don’t get it. The sex on TV is not the sex in real life, be it on Showtime or the Hallmark channel. It’s time to set the record straight and for some sex health 101.

1) Vaginal penetration is not the gold-standard for orgasm

The history and fallacies surrounding vaginal-only orgasm could fill a novel, and have.1 If you are interested in a shortened version check out this fun musical rendition. We’ll leave the social commentary and just talk about the simple facts. The vagina is just one of many erogenous zones that can lead to orgasm. And conventional heterosexual penetrative intercourse is not the only way to get there. Biology can help lead us down some alternative paths. The vagina, a passageway from the outside world to the uterus, is built more for transport than sensation. The sensory map for the vagina is very vague and follows the visceral sensation back to the brain. Think about it, would you want to have precise sensation for tissue that needs to stretch >3x its normal size for birth3 I don’t think so. Now, the clitoris on the other hand, no pun intended, has the highest density and precision of receptors in the whole body.4 All bodies in fact, as the glans clitoris has almost five times the receptor density as the glans penis.5 Since the glans clitoris is on the outside of the pubic bone, it is not stimulated during penetration alone. And the clitoris is just one option on a road to orgasm. Check out this blog to get some more ideas. Or take a look here to learn how sex is more than just a P in a V.

2) Sex on the beach, a tasty drink, yes, an enjoyable experience, I think not, more like sandpaper in the crotch

Now what is more romantic than the sunset, a lover’s embrace, waves lapping at your feet, and sand…getting everywhere. For the brave who have tried, you would find that it’s not so comfortable, for either party. Genital tissue is thin and sensitive for a reason, so if anything rough is rubbed on it over and over again…well you can imagine the ramifications. Also, chemical irritants can wreak havoc on genital tissue, especially the vagina. This brings me to those hot and steamy pool scenes. The pool- fine to swim in, the labia provide a type of leak-proof seal. Unfortunately with penetrative sex, chlorine, and other pool floaties, get a little too up close and personal. The vagina has a delicate hormonal and bacterial balance that maintains its pH at a happy 3.8. It even has its own cleaning system. Throwing chlorinated water, a strong sanitizer with a pH 7.2, or pretty much anything into the vagina, can cause problems. For a little more info about what makes for good vaginal health, take a look at our most popular blog: How your vagina is supposed to smell, 50,000 reads and counting.

3) The walk of shame is not the only repercussion of an unprotected one-night stand

The walk of shame may be enough of a deterrent for some, but there are a couple other reasons you may want to rethink unprotected stranger sex.. One is fairly obvious…pregnancy. There are few movies that broach the subject. Obvious Child and Knocked Up use this “unexpected” plot twist to show viewers the “comical” experience of unplanned pregnancy. There are also more true-to-life renditions, like Precious or this BuzzFeedYellow film. However, these seem to be more the exception than the norm. Another missed opportunity for theatrical conflict, STIs! In the top 200 films of all time (rated by IMDB), there was only one mention of condom use, and that was just in reference to birth control.6 I’m more of a rotten tomatoes fan myself, but you get the point. This, along with the recent rejection of California’s Prop 60 condom mandate for pornographic films, exemplifies how condoms aren’t seen as sexy and STIs are not considered a serious health risk. This is even more disparate from reality since in the US we are seeing a 20-year record high in the number of chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis cases.7 And these rates just keep increasing each year. All this to say, can we please just have a movie with a dude who puts on a condom for some good clean fun…I think Ryan Gosling could make it work.

4) Not all good sex is easy sex

Hopefully this isn’t too surprising. Not all holes are created equal. Sometimes it takes a little maneuvering to get the angle right. I chuckle every time someone just slips in during penetrative sex- especially if it’s a first-time kind of deal. In the real world, it’s normal to have to recalibrate to match your partner. That’s part of what makes sex fun. Also if you need something to grease the wheels a bit, which is normal too, try some lubrication. Young and old alike, lube is your friend. But before you reach for the KY, check out some better recommendations for a good time. Also, sex is messy, so sex requires clean up. If I chuckle at the slip-in, I LOL at the roll over and go to sleep when it’s all done. Umm, does every starlet have a UTI and a wet spot she curls up in? And does every hero have a split stream? It’s not that unreasonable to add a little girl-sitting-on-the-toilet pee scene, à la Girls, or if that is too crude, how about a shower scene to get everything spic and span and sexy. Remember, we’re talking just water here, no soap in the nether regions, please.

5) Sex is not just for the young, beautiful and belly-free

This is more of a comment on Hollywood as a whole. I’m sure we can all agree that what we see on TV does not match what we see on real bodies. And, no, Gwyenth’s egg is not going to get you there (you know I had to fit that in somewhere 😉 ). But I just want to remind everyone that sex is for everyone. It looks different for everyone. Whether we’re talking intercourse, or outercourse….uppercourse or lowercourse, let it be consensual, let be fun and let it be real. So go get yours!

Bibliography:

- Gerhard J. Revisiting “the myth of the vaginal orgasm”: The female orgasm in American sexual thought and Second wave feminism. Feminist Studies. 2000;26(2):449. doi:10.2307/3178545