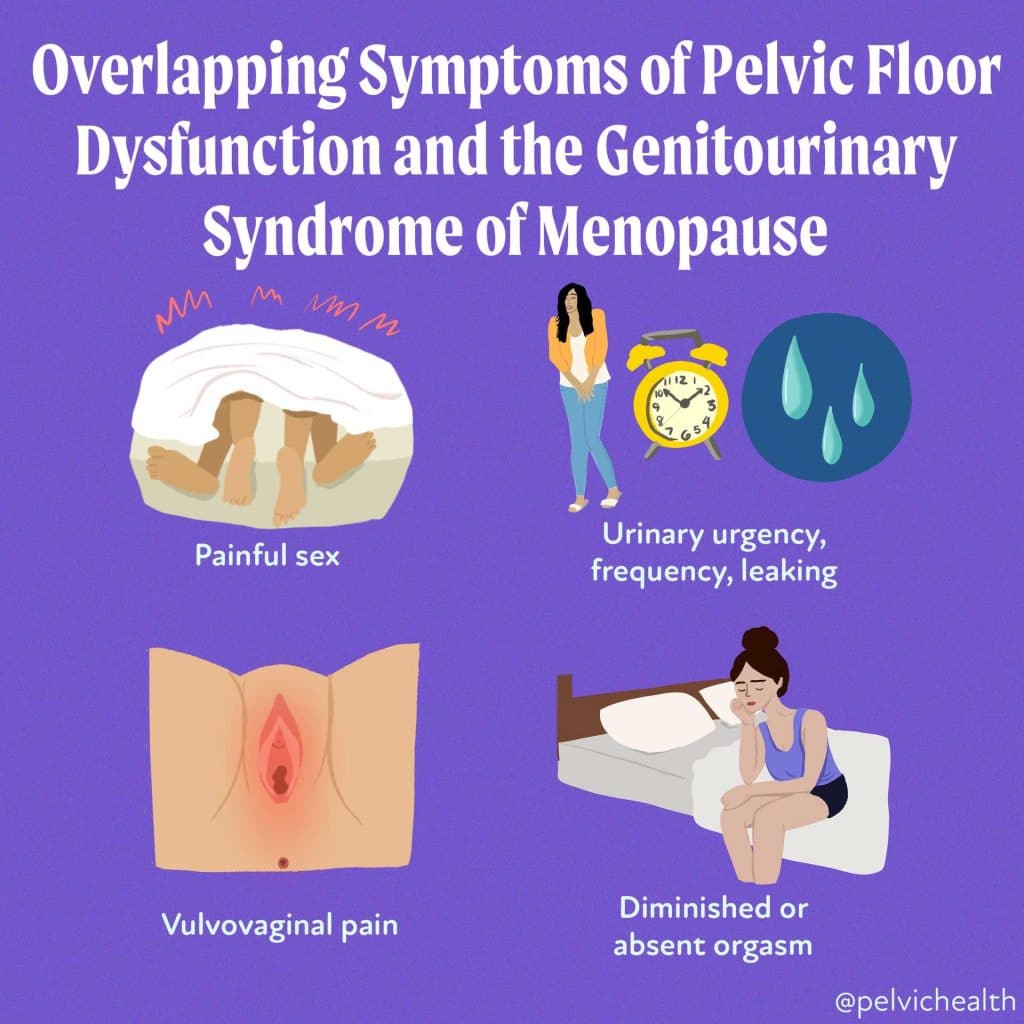

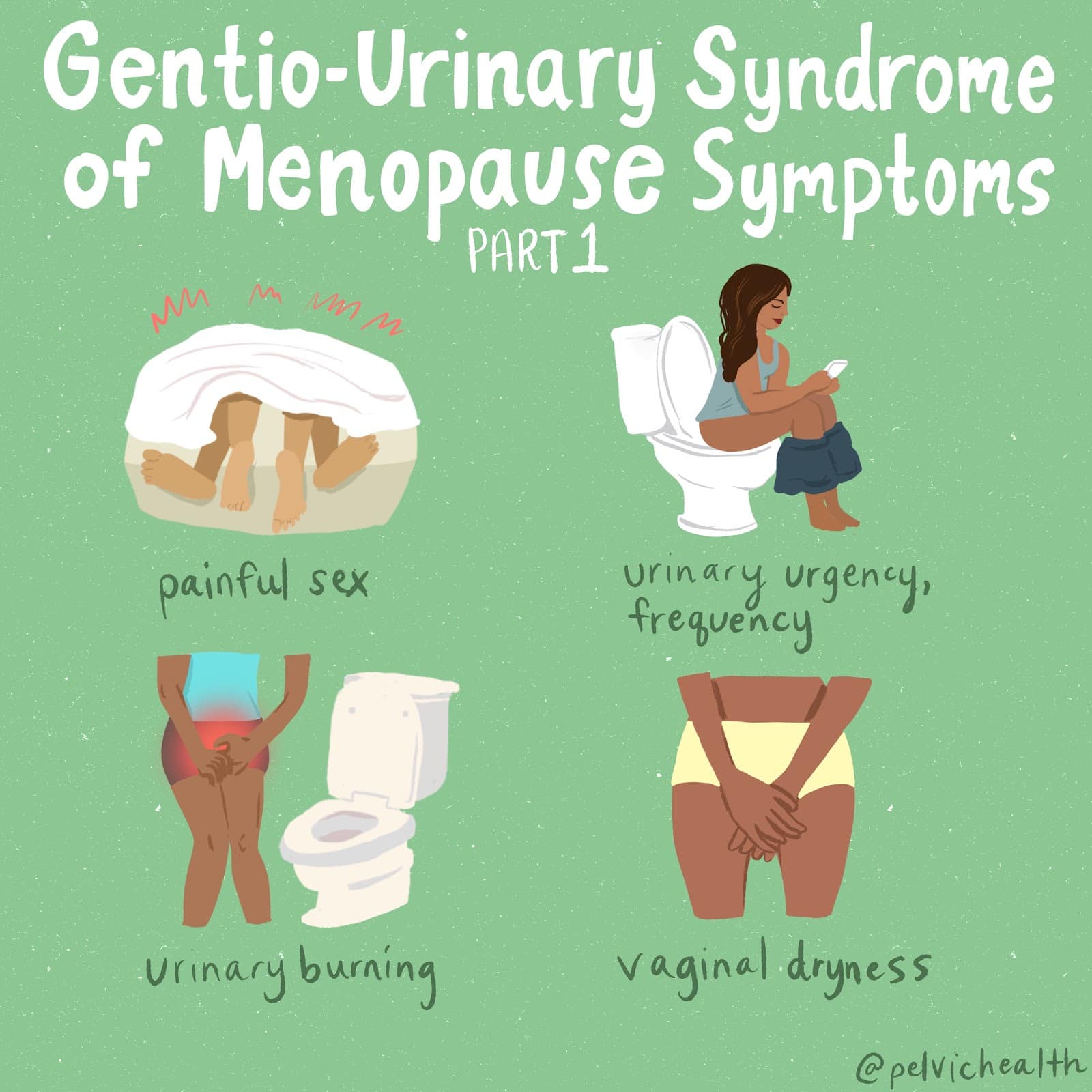

Menopause is more than just hot flushes, night sweats and mood changes! Even though 50% of the population goes through menopause the majority of people and healthcare providers are under-informed about menopause and safe and effective treatments. Too many people are suffering unnecessarily. Perimenopause, the precursor to menopause begins in the 40’s for most people and most women will be in menopause by their early 50’s. Beyond the systemic symptoms of menopause people will start to experience more subtle genitourinary symptoms that will continue to worsen over time if untreated. Painful sex, urinary urgency, frequency, leaking and burning, recurrent vaginal and urinary tract infections and vaginal dryness are symptoms of the Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM). The symptoms of GSM are also symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, which almost 50% of women suffer by the time they are in their 50s.

Systemic menopause symptoms are often treated with systemic hormonal therapy. This may not be sufficient for people developing GSM symptoms. The North American Menopause Society recommends vaginal estrogen for women in menopause to help counter GSM symptoms.

Menopause is more than just hot flushes, night sweats and mood changes! Even though 50% of the population goes through menopause the majority of people and healthcare providers are under-informed about menopause and safe and effective treatments. Too many people are suffering unnecessarily. Perimenopause, the precursor to menopause begins in the 40’s for most people and most women will be in menopause by their early 50’s. Beyond the systemic symptoms of menopause people will start to experience more subtle genitourinary symptoms that will continue to worsen over time if untreated. Painful sex, urinary urgency, frequency, leaking and burning, recurrent vaginal and urinary tract infections and vaginal dryness are symptoms of the Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM). The symptoms of GSM are also symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, which almost 50% of women suffer by the time they are in their 50s.

Systemic menopause symptoms are often treated with systemic hormonal therapy. This may not be sufficient for people developing GSM symptoms. The North American Menopause Society recommends vaginal estrogen for women in menopause to help counter GSM symptoms.

Differential Diagnosis:

GSM or Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction and GSM include:

- Urinary urgency, frequency, burning, nocturia

- Feelings of bladder or pelvic pressure

- Painful sex

- Diminished or absent orgasm

- Difficulty evacuating stool

- Vulvovaginal pain and burning

- Pain with sitting

An informed healthcare provider – whether a pelvic floor physical and occupational therapists or medical doctor – can do a vulvovaginal visual examination, a q-tip test to establish pain areas, and a digital manual examination to identify pelvic floor dysfunction, hormonal deficiencies, and pelvic organ prolapse. All women will experience GSM if enough time passes without appropriate medical management. The majority of people do not realize that menopausal women can benefit from a pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy examination to address the musculoskeletal factors that are also making them uncomfortable. The combination of pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy and medical management is key to help restore pleasurable sex and eliminate urinary and bowel concerns!

FACTS

From: https://www.letstalkmenopause.org/further-reading

- 6000 women enter menopause everyday

- 50 million women are currently menopausal in the US

- 84% of women struggle with genital, sexual and urinary discomfort that will not resolve on its own, and less than 25% seek help

- 80% of OBGYN residents admit to being ill-prepared to discuss menopause

- GSM is clinically detected in 90% of postmenopausal women, only ⅓ report symptoms when surveyed.

- Barriers to treatment: women often have to initiate the conversation, believe that the symptoms are just part of aging, women fail to link their symptoms with menopause.

- Only 13% of providers asked their patients about menopause symptoms.

- Even after diagnosis, the majority of women with GSM go untreated despite studies demonstrating a negative impact on quality of life. Hesitation to prescribe treatment by providers as well as patient-perceived concerns over safety profiles limit the use of topical vaginal therapies.

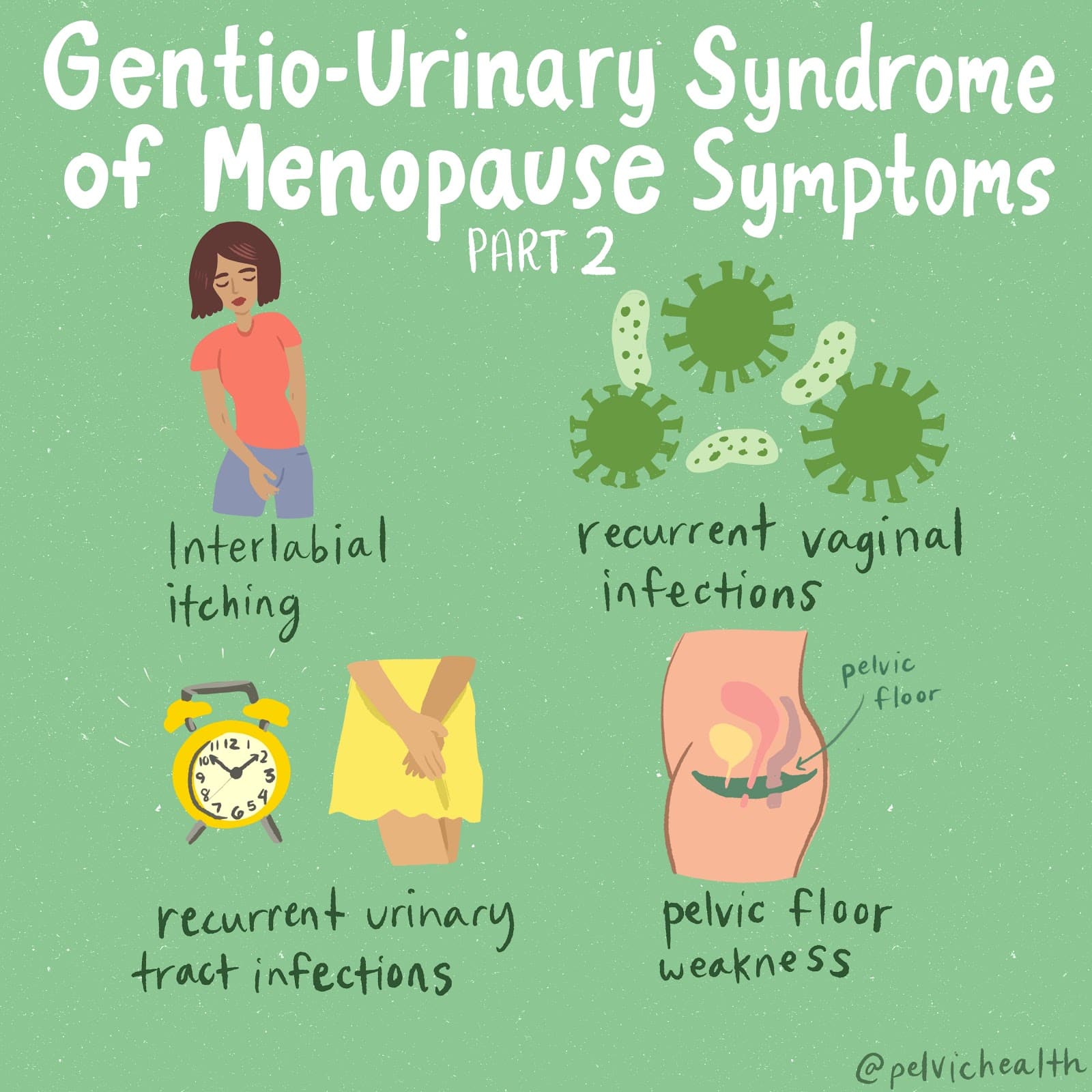

Hormone insufficiency can result in interlabial and vaginal itching. Other dermatologic issues such as Lichen Sclerosus and cutaneous yeast infections are just two of the many factors to also be considered.

Unfortunately people are vulnerable to recurrent vaginal and urinary tract infections in menopause due to:

- pH and tissue changes

- incomplete bladder emptying

- pelvic organ prolapse compromising urinary function

Recurrent infections are a leading cause of pelvic floor dysfunction! They must be stopped or the noxious visceral-somatic input can cause further pain and dysfunction after the infection is cleared. Furthermore, if the infections are left untreated without hormone therapy infections continue to occur and the consequences can be severe. Women can develop unprovoked pain, sex may be impossible, and undetected UTIs can lead to kidney problems and more sinister issues.

We encourage people to work with a menopause expert to monitor, prevent, and treat these issues as they are serious and treatable! We need to normalize the conversation about what happens during GSM, it is nothing to be embarrassed about and with the right care vulva owners can live their best lives! Pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy and medical management go hand in hand.

Treatment:

How We Can Help You

If you are having issues with your sexual function, it is in your best interest to get evaluated by a therapist for pelvic floor therapy, so they can establish what part, if any, of your pelvic floor may be contributing to the symptoms you are experiencing. During the course of the examination, the physical and occupational therapists will talk to you about your medical history and symptoms, including what you have been previously diagnosed with, the treatments or therapies you have had, and how effective or ineffective these therapies have been for you. It is significant to mention that we fully comprehend what you’ve been dealing with and that the majority of individuals are angry by the time they make it to see us. The physical and occupational therapists will conduct an evaluation of the patient’s nerves, muscles, joints, tissues, and movement patterns while doing the physical examination. After the examination is finished, your therapist will go over the results of the assessment with you. The physical and occupational therapists will conduct an evaluation to determine the cause of your symptoms and will establish both short-term and long-term therapy goals based on the results of the evaluation. Physical therapy treatments are typically administered between once and twice each week for a period of around 12 weeks. Your physical and occupational therapists will assist you in coordinating your recovery with all the other experts on your treatment team. They will provide you with an exercise regimen to complete at home and the sessions you attend in person. We are here to assist you in getting better and living the best life possible.

For more information about IC/PBS please check out our IC/PBS Resource List.

Treatment:

How We Can Help You

If you are having issues with your sexual function, it is in your best interest to get evaluated by a therapist for pelvic floor therapy, so they can establish what part, if any, of your pelvic floor may be contributing to the symptoms you are experiencing. During the course of the examination, the physical and occupational therapists will talk to you about your medical history and symptoms, including what you have been previously diagnosed with, the treatments or therapies you have had, and how effective or ineffective these therapies have been for you. It is significant to mention that we fully comprehend what you’ve been dealing with and that the majority of individuals are angry by the time they make it to see us. The physical and occupational therapists will conduct an evaluation of the patient’s nerves, muscles, joints, tissues, and movement patterns while doing the physical examination. After the examination is finished, your therapist will go over the results of the assessment with you. The physical and occupational therapists will conduct an evaluation to determine the cause of your symptoms and will establish both short-term and long-term therapy goals based on the results of the evaluation. Physical therapy treatments are typically administered between once and twice each week for a period of around 12 weeks. Your physical and occupational therapists will assist you in coordinating your recovery with all the other experts on your treatment team. They will provide you with an exercise regimen to complete at home and the sessions you attend in person. We are here to assist you in getting better and living the best life possible.

For more information about IC/PBS please check out our IC/PBS Resource List.

Part I in the “Demystifying Pudendal Neuralgia” Series

For so many the term “pudendal neuralgia” conveys a frightening and mysterious chronic pain diagnosis. And to be sure, at one time, receiving a diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia, or “PN” as it’s commonly called, was truly terrifying, especially considering that it was against the backdrop of a medical community that didn’t have answers and an online community rife with misinformation.

However, “pudendal neuralgia” literally means “shooting, stabbing pain along the distribution of the pudendal nerve.” So in reality, pudendal neuralgia is not a dark, mysterious diagnosis, it’s simply pain anywhere along the nerve that innervates the pelvic floor.

While progress has been made in the treatment of PN over the past decade, there continues to be a tremendous amount of confusion swirling around the diagnosis, not the least of which is the massive confusion surrounding the difference between the diagnosis of PN versus the diagnosis of PNE and what is the appropriate course of treatment for each.

In this post, I’m going to tackle those two points. But, that’s not the last you’ll hear about PN on this blog. It’s a topic I’ve spent my career embroiled in, and it’s one that I’m passionate about.

So this post marks the beginning of what will be a four-part series on PN. Further posts in the series will tackle PT as a treatment for PN, and a two-part interview with Drs. Mark Conway and Michael Hibner.

A Tortuous Course

Before I get into PN versus PNE, I want to first give you a brief explanation of the physiology of the pudendal nerve and the diagnosis of PN.

The pudendal nerve is a large nerve that arises from the S2, S3, and S4 nerve roots in the sacrum, and divides into three branches—the inferior rectal nerve, the perineal branch, and the dorsal clitoral/penile branch. The nerve travels a tortuous course through the pelvis to innervate:

• the majority of the pelvic floor muscles,

• the perineum,

• the perianal area,

• the distal third of the urethra

• part of the anal canal

• the skin of the vulva, the clitoris, portions of the labia in women,

• and the penis and scrotum in men.

The pudendal nerve travels a torturous course through the pelvis.

Patients with PN can have tingling, stabbing, and/or shooting pain anywhere in the territory of the nerve. Symptoms include vulvar or penile pain, perineal pain, anal pain, clitoral pain, and pain at the ischial tuberosities as well as pain with bowel movements, urination, and orgasm.

One of the things that make the pudendal nerve so unusual is that it doesn’t just have motor and sensory fibers like other nerves that exist outside of the brain and spinal cord, it also has autonomic fibers.

Here’s the significance of this unusual quality: Motor and sensory fibers innervate somatic structures, like muscles, giving us voluntary control over them. Whereas structures innervated by autonomic fibers are not under our voluntary control. The heart, lungs, and GI tract are examples of such structures.

So it’s thanks to the autonomic fibers of the pudendal nerve that our pelvic floor muscles always maintain a degree of tone, which enables us to remain continent. But we do have the ability to override the tone in our pelvic floor muscles and further contract or relax them when we wish. So, the pudendal nerve is only partially under autonomic control.

What is the relevance of this to our discussion of PN symptoms? Well, it’s because of these autonomic fibers that patients with PN can experience disturbing feelings of sympathetic upregulation when their pain spikes. Symptoms such as:

• an increase in heart rate,

• a decrease in the mobility of the large intestines,

• a constriction of blood vessels,

• pupil dilation,

• perspiration,

• a rise in blood pressure

• goosebumps, and

• sweating, agitation, and anxiety.

I’ve had many patients that have reported these symptoms. Many have told me that they thought they were going crazy or were having an anxiety attack at those times. So it’s important that patients are aware of this feature of the nerve. They’re not crazy! And with the proper treatment, these symptoms can be stopped.

PN vs.PNE

In order to best understand the differences between PN and PNE, you need to have a sense of the history of both diagnoses.

I began working with pelvic pain patients in 2001. Back then, nearly every patient I saw had been suffering for at least five years, often longer, had seen an average of ten other providers, and was in tremendous pain. Across the board, these patients had been dismissed, misdiagnosed, and mistreated.

However, when I came into the pelvic pain picture, a shift was happening in the medical community. It was sinking in that pelvic pain was a valid health issue that needed to be addressed. “PN,” “vulvodynia,” and “IC” were all diagnoses that had individually made their way onto the scene, but collectively they were now being handed down to patients with more frequency. So, for instance, a patient who had been told her symptoms were “all in her head” was now given a diagnosis of “PN.”

What did it mean to be diagnosed with PN back then?

Because this was a patient demographic that had been mistreated for so long, for the majority of these patients, their pain had become ingrained in their nervous systems. So as a result, the treatments that were administered, such as nerve blocks, medication and PT were not successful because they were only aimed at the periphery of the patients’ pain, not the peripheral and central nervous systems. Plus, there wasn’t the same level of understanding of the myofascial musculoskeletal component of pelvic pain or the need for a multidisciplinary approach to treatment that there is today.

Then sometime around 2003, pudendal nerve entrapment or “PNE” became the diagnosis du jour. PNE was first mentioned in 1988, but became popular as a diagnosis around 2003, most likely because of chat rooms about the condition on the Internet.

PNE is most commonly defined as a physiological entrapment of the pudendal nerve that requires surgical release. While “PNE” can certainly cause PN, it’s far from the only cause. However, one of the symptoms of PNE at the time was “pain with sitting.” Therefore, anyone who had pain with sitting, all of a sudden had nerve entrapment. Plus, the terms “PN” and “PNE” were suddenly becoming used interchangeably. So too often, as soon as there was the inkling that the pudendal nerve was involved in a patient’s pain, he or she was told entrapment was the cause and three nerve blocks and decompression surgery was the answer.

Clearly, providers were systemically over diagnosing patients with PNE. Intentions were in the right place. Providers wanted to successfully diagnose and treat their patients, and patients, for their part, wanted to get better.

PNE had emerged in the literature as a diagnosis in the 1980s when almost nothing was known about myofascial pain and chronic pain syndromes in general. Surgeons and anesthesiologists in Europe were the first ones to take an interest in PNE, and as a result the treatment methods that were developed focused on nerve blocks and decompression surgery.

Electrophysiological testing also fell within the bailiwick of this particular group of physicians, so these are the testing methods that were used to determine PN/PNE. (Remember, for a period of time the two became muddled together.) So if PN/PNE was suspected, a pudendal nerve terminal motor latency test or a “PNTMLT”, which is a nerve conduction velocity test was administered to “verify” the diagnosis. Next, patients were given three nerve blocks and medication.

For its part, A PNTMLT is a test that measures nerve conduction velocity times. The test is administered by inserting a small needle into the ventral external anal sphincter (the portion innervated by the perineal branch of the pudendal nerve). The doctor than inserts a gloved finger with an electrode into the anus and delivers a charge to the perineal branch of the pudendal nerve at the ischial spine. The recording needle electrode captures the amount of time it takes for the signal to get from the ischial spine to the sphincter. If the time is “delayed” the test is considered to be positive. This test is incredibly painful and can cause a flare that can last for weeks. Plus, at the time of testing, the secondary muscle spasm associated with the pain of the test often makes its readings unattainable.

Historically, with or without the results of a PNTMLT, the next step to treating PN/PNE was to administer nerve blocks and medications. The nerve blocks were painful and provided about four hours of relief at best, and the medication either did not help or caused side effects that were worse than the pain itself.

When that protocol failed (and it almost always did for the above mentioned reasons), the next step on the treatment train was decompression surgery. Patients were told the longer they waited to get the surgery the worse their pain would become. To further complicate matters, for a time, the only surgeons who did the surgery were in France. So patients were traveling to France en masse to have the surgery done.

Fast forward to the present day. Today there’s been a great deal of progress made in our understanding of PN and PNE.

And one of the biggest discoveries is that there is no way to know whether a patient has pudendal nerve entrapment prior to operating. I’m going to say that again because I think it bears repeating: There is no way to determine whether or not someone has pudendal nerve entrapment prior to surgery.

And in fact, the only way to know with any certainty whether there was indeed an entrapment post-surgery is a post-operative finding of pain relief. This is according to research conducted by neurosurgeon, Prof. Roger Robert, and neurologist and urologist, Dr. J.J. Labat, the team of French surgeons that developed the initial surgical technique for the PNE decompression surgery.

No Way to Know

By 2008, several groups of leading PN experts conducted studies and discredited the electrophysiological tests as diagnostic tools of PN/PNE. (A great paper that summarizes the numerous studies that led to the invalidation of the tests is “What is the Place of ENMG Studies in the Diagnosis and Management of Pudendal Neuralgia Related to an Entrapment Syndrome?” by Lefaucher, J.P., Labat, J.J., Amerenco, G., et al.)

In early days when the medical community was working to make heads or tails of a PN/PNE diagnosis, it seemed logical to apply the testing to the diagnosis. After all, it was the protocol used in other parts of the body for neuralgia and entrapment. So why wouldn’t it work for the pudendal nerve? The reason is that pudendal neuralgia and PNE is a sensory problem – pain – and this test measures the speed of motor fibers. We can not correlate the nerve conduction speeds of pain.

There are surgeons who say they believe that they can see entrapment when they open the patient up, that they can see nerves that are grey and look frayed; however, there’s not that much correlation between the levels of pain the patient has, and the doctor’s visual. Plus, surgeons are not operating on asymptomatic individuals, so we don’t know if the asymptomatic population looks the same anatomically. Therefore, it’s a big assumption to say you can see entrapment when we don’t know what “normal” is.

Today PN patients are having MRIs done. (More details on this in the fourth post in this series.) For their part, MRIs can show that there is swelling around the nerve. However, issues other than entrapment, can cause swelling, so again, this is not a appropriate diagnostic test for PNE.

So although patients continue to have these tests done and even to rely on them for proof of entrapment and PN, the fact of the matter is that all the accepted thinking in the field, even by the surgeons who perform the decompression surgery, is that the tests do not confirm either entrapment or pudendal neuralgia.

The History is the Key

The most important factor in deciding whether or not a patient has a possible entrapment is the patient’s history. In fact, this is the thinking espoused by one of the country’s leading PN physicians, Dr. Michael Hibner.

For example, if a patient who had no pelvic pain, had pelvic reconstructive surgery, and woke up from the surgery with shooting, stabbing vaginal pain, then that is likely an entrapment that probably needs to be surgically released. However, if a patient has had seven yeast infections in a row, and develops vaginal burning, it’s not reasonable to conclude that a ligament is entrapping the nerve and causing those symptoms. Connective tissue dysfunction and hypertonic muscles are more likely the cause.

So before a patient, or a surgeon for that matter, goes forward with a nerve decompression surgery, they need to be sure that the patient’s history makes sense.

Some in the medical community, myself included, believe that there are only two hard and fast situations where a nerve will likely be entrapped. One is an anatomical deviation that the patient is born with, and the other is as a result of a problematic pelvic surgery, such as a hysterectomy or a pelvic reconstructive surgery to correct a cystocele, rectocele or prolapse. If a patient has a slow, insidious onset of pain that eventually becomes burning, then that’s probably not entrapment but rather myofascial pelvic pain that is affecting the pudendal nerve.

When PN Plays a Role

By this point, I hope that I have made it clear that the diagnoses of PN and PNE are not interchangeable and that there are no tests that can show if the pudendal nerve is entrapped or that a patient even has PN.

So then how do you know if you have PN?

Today, a diagnosis of PN is a clinical diagnosis, which means the diagnosis is based on signs, symptoms and medical history of the patient rather than on laboratory examination or medical imaging. Generally, PN symptoms are said to include burning, stabbing and/or shooting pain anywhere in the territory of the nerve.

Plus, a provider can examine the patient’s pelvic floor internally via the rectum or the vagina and upon examination test the pudendal nerve by performing a technique called a “Tinel’s Sign. A Tinel’s Sign is a way to detect irritated nerves. It is performed by lightly tapping over the nerve to elicit a sensation of tingling or “pins and needles” in the distribution of the nerve.

As you may have already realized, many of these symptoms overlap with symptoms of other pelvic floor problems. This can make it difficult to arrive at a definitive, iron-clad diagnosis of PN.

However, at the end of the day, as is the case with most pelvic pain syndromes, not being able to have a written-in-stone diagnosis isn’t a big loss because with pelvic pain, the diagnosis doesn’t dictate a treatment protocol. In fact, there is no standard, one-size-fits-all protocol for treating PN. Not to mention the fact that more often than not, there is going to be a combination of causes. So at the end of the day, if you think about it, “pudendal neuralgia” is more of a symptom than a diagnosis, anyway.

Remember, “pudendal neuralgia” means pain along the distribution of the pudendal nerve. So saying “I have pudendal neuralgia” is analogous to saying “I have burning or stabbing clitoral, vaginal, or penile pain.”

So when it comes to pudendal neuralgia, the most important course of action is to figure out the underlying causes, and then figure out what needs to be done to treat them.

PN Treatment Today

In wrapping up this post, after having spent so much time talking about what not to do when it comes to PN, I’d like to spend some time discussing the actions I do recommend for patients when pudendal neuralgia is suspected. Thankfully, today patients have more reasonable, comprehensive treatment options. The best course of action is for them to approach their treatment with a multidisciplinary team approach in mind.

PT

An important player in on a multidisciplinary team to treat PN is a pelvic floor physical and occupational therapists.

At the end of the day, pudendal neuralgia is a myofascial pain syndrome that affects the nerve that innervates the pelvic floor musculature and viscera, so a PT who is expert at treating the pelvic floor should be able to address why that nerve is irritated.

However, many patients are afraid that PT will further irritate their pudendal nerve. Perhaps they’ve read on an online message board that this has happened to others with similar symptoms. Here’s the deal: PTs do not learn about treating the pelvic floor in PT school let alone how to palpate the pudendal nerve. So if a patient sees a PT that does not know their way around the pudendal nerve than yes, that PT could irritate their nerve. That’s why it’s important for the patient to do his or her homework and make sure the PT has proper level of expertise to treat them. The physical and occupational therapistss at the Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Center are specifically trained to help people recover from complex pelvic pain syndromes, including pudendal neuralgia. (Our next post will delve much more deeply into PT for PN.)

Medication

There are a handful of medications that are helpful for PN. One group is SNRIs, which are aimed at calming the central nervous system, such as Cymbalta. Other anticonvulsant drugs such as Lyrica, and Neurontin are also often top choices in this group.

Another group includes tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline and desiprimine.

When working with meds, patients need to realize that they must get to the proper therapeutic dose for the proper length of time before they will experience a medication’s effectiveness. In addition, just because the medication doesn’t take away all of their pain, this doesn’t mean it is not having a therapeutic effect.

Nerve Blocks

In the past, I would have said that pudendal nerve blocks are not therapeutic. However, I believe the reason they did not work for my patients in the past is that the patients that were getting them early most likely had central sensitization due to the severity and the chronicity of their pain, and therefore any treatment directed at the periphery, whether a block, medication, or PT was not going to be as effective as it could be.

However, today, patients are getting diagnosed much earlier in the game; therefore, I believe all of the treatments aimed at the periphery, such as nerve blocks, are having higher success rates.

That said, nerve blocks should never be a patient’s only course of treatment. They are not going to be a silver bullet cure-all. Much of the time, the lasting effect on the patient’s pain is very minimal. If there is a long term effect, it will be that once the anesthetic wears off, the patient will have a little less sensitivity.

So bottom line: my advice is that if a patient has access to a physician in their community who has a reputation as being an expert at administering nerve blocks, and their insurance covers the block, then they should give it a try with the expectation that at best it may help and at worst it may cause a temporary flare. However, if the patient has to travel to another state and spend thousands of dollars to get it done, the possible benefit is not likely worth the travel and expense.

Botox for PN

Botox is very good for muscle hypertonis, which is associated with PN, so if a patient (typically with the direction of their PT), is suspicious that the obturator internus is a large part of their pain/nerve irritation, then Botox may make sense.

A good test run is to have the physician first inject lidocaine into the area to see if there is a positive effect. If some or all of the patient’s pain is reduced or eliminated during the first hour after the injection it may make sense to then inject Botox. One reason for this approach is that Botox is quite expensive, so it’s a good idea to make sure it’s going to be injected into an area that is relevant.

I mention the obturator specifically because that is a muscle that is commonly involved in PN because part of the Alcock’s Canal is made up of the aponeurosis of the obturator internus and so if there is compression in that canal, decreasing the hypertonis will take some of the pressure off of the nerve in the same way that decompression surgery would. So in fact, in such a situation where the nerve is compressed, either Botox or manual therapy can serve to free it up instead of surgery.

I hope this post has fulfilled my goal of shedding light on a few areas of the PN diagnosis that continue to cause confusion. It’s a complicated diagnosis that thankfully is beginning to make more sense, but there’s still a lot of work to do. Speaking of, stay tuned for the next post in our pudendal neuralgia series, which will focus on the

role of physical and occupational therapy in treating pudendal neuralgia . Be sure and subscribe to the blog if you haven’t already. Our book, Pelvic Pain Explained is a resource manual that helps readers understand how pelvic pain develops, it helps navigate in-clinic and at-home treatment options for men and women. Please also check out our Pudendal Neuralgia Resource List, complete with videos, blogs, and podcasts.

In the meantime, if you have any questions or comments, please leave them in the box below. I look forward to hearing from you.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Are you unable to come see us in person? We offer virtual physical and occupational therapy appointments too!

Due to COVID-19, we understand people may prefer to utilize our services from their homes. We also understand that many people do not have access to pelvic floor physical and occupational therapy and we are here to help! The Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Center is a multi-city company of highly trained and specialized pelvic floor physical and occupational therapistss committed to helping people optimize their pelvic health and eliminate pelvic pain and dysfunction. We are here for you and ready to help, whether it is in-person or online.

Virtual sessions are available with PHRC pelvic floor physical and occupational therapistss via our video platform, Zoom, or via phone. The cost for this service is $75.00 per 30 minutes. For more information and to schedule, please visit our digital healthcare page.

In addition to virtual consultation with our physical and occupational therapistss, we also offer integrative health services with Jandra Mueller, DPT, MS. Jandra is a pelvic floor physical and occupational therapists who also has her Master’s degree in Integrative Health and Nutrition. She offers services such as hormone testing via the DUTCH test, comprehensive stool testing for gastrointestinal health concerns, and integrative health coaching and meal planning. For more information about her services and to schedule, please visit our Integrative Health website page.

PHRC is also offering individualized movement sessions, hosted by Karah Charette, DPT. Karah is a pelvic floor physical and occupational therapists at the Berkeley and San Francisco locations. She is certified in classical mat and reformer Pilates, as well as a registered 200 hour Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga teacher. There are 30 min and 60 min sessions options where you can: (1) Consult on what type of Pilates or yoga class would be appropriate to participate in (2) Review ways to modify poses to fit your individual needs and (3) Create a synthesis of your home exercise program into a movement flow. To schedule a 1-on-1 appointment call us at (510) 922-9836

All my best,

Stephanie

About Stephanie Prendergast: Stephanie is the co-founder of the Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Center, president of the International Pelvic Pain Society, and an organizing member of The World Congress on Abdominal and Pelvic Pain. She has written extensively on the topic of pudendal neuralgia and teaches a course titled “Demystifying Pudendal Neuralgia: A Physical and Occupational Therapists’s Approach” for physical and occupational therapistss.

Tony is one of those people who seem superhuman. In his early 30s, he’s lean and athletic. When he isn’t chasing after one of his three young children or helping to run a successful family business, you can find him surfing, hunting, snowboarding, golfing, swimming, or playing basketball.

It’s hard to believe that at one time, this guy who has such a passion for living was all but convinced that his life was over. But there was a time, not all that long ago, when he was sure that he’d never participate in another sport that he loved, let alone be able to work or even have relations with his wife.

It was on an unseasonably warm afternoon in February back in 2003 when Tony’s full and happy life took an unexpected detour. On that day, as usual, he was in active mode, attempting to pull off the perfect handstand when all of a sudden, he felt a sharp pinching pain in his lower abs.

Three doctors later, he was diagnosed with an “abdominal strain” and prescribed core-strengthening exercises. The exercises made his pain worse, and in a matter of weeks his symptoms exploded. The sharp pain in his abs snowballed into pain with sitting, constant perineum and groin pain, and a burning pain at the tip of his penis.

Unable to find any answers from the doctors he visited, he turned to the Internet. That’s when the fear and panic set in. After spending hours online, he discovered that his symptoms were a match with a disorder called “pudendal nerve entrapment”or “PNE.”

After reading a litany of stories about PNE, he was convinced that he needed surgery as soon as possible to free his entrapped pudendal nerve. Otherwise, according to the information he was uncovering, his symptoms would continue to worsen. He even contacted one of the doctors mentioned in the online forums who performed the surgery. The doctor encouraged him to fly out and schedule the surgery with him right away.

“I was terrified,” he recalls, “I was reading all of these horror stories, and I believed that if I didn’t get surgery as soon as possible, I would end up impotent and incontinent. Even with surgery I was afraid of what my life was going to become.”

However, before he signed up for surgery, he decided to see one more doctor in San Francisco. Thankfully, that doctor was one of the few in the country in the know about male pelvic pain. The doctor explained that trigger points and muscle spasms in the pelvic floor—and in Tony’s case, in the abdomen—have the potential to cause all of the symptoms he was experiencing. The doctor then prescribed pelvic floor PT to treat his pain. Finally, he was getting what seemed like a reliable explanation for what was happening to him. Plus, there was a treatment option available that was much more conservative than going under the knife.

“I admit at first I didn’t believe PT was going to help me,” he says. “But I decided I would just do it as a final effort before I got the surgery.”

After the first session with Stephanie, Tony felt a slight bit of relief. Ultimately, with regular PT sessions—at first twice weekly and then weekly—his pain and symptoms began to diminish, until eventually they were gone altogether.

“Today I have zero pain,” he says. “But it didn’t go away overnight,” he is quick to add. “It took time, patience, and a lot of commitment. And there were times during my sessions with Steph when I would break down because I was still so anxious about all that I had read on the Internet.”

Tony began PT with Stephanie in January of 2004, and by January of 2006, he was completely symptom-free. Today he is living an unrestricted, active life without pain.

Unfortunately, Tony’s struggle with pelvic pain is all too common. Research shows that between 8% and 10% of the male population suffers from pelvic pain. But that number is likely higher because studies also show that 50% of men will deal with prostatitis at some point in their lives, and pelvic pain in men is consistently misdiagnosed as prostatitis.

Tony’s ordeal is also common in that, because he couldn’t get answers from his doctors, he turned to the Internet for information, a move that led him down a dark road of misinformation. The reality is that men with pelvic pain have an even harder time getting a proper diagnosis and treatment than women with pelvic pain.

For one thing, the medical community systematically misdiagnosis any pelvic pain symptom in men, —whether perineal pain, post-ejaculatory pain, urinary frequency, or penile pain—as a prostatitis infection, despite the absence of virus or bacteria.

The absence of a virus or bacteria simply means a switch in diagnosis from “prostatitis infection” to “chronic nonbacterial prostatitis.” Typically, from there the doctor writes out an Rx for a few months worth of antibiotics and the drug Flomax, and the patient is sent on his way.

In the beginning, because antibiotics have an analgesic effect, patients will actually feel a tiny bit better. But before long the effect wears off, and they’re right back where they started; in pain with no relief.

What’s so maddening about this misdiagnosis loop is that in 1995, the National Institute of Health (NIH) clearly stated that the term “chronic nonbacterial prostatitis” does not explain nor is even related to the symptoms these men suffer. To describe the symptoms they actually do suffer with, the NIH adopted the term: “chronic pelvic pain syndrome.”

The symptoms the NIH listed as being those of pelvic pain are: painful urination, hesitancy, frequency, penile, scrotal, rectal, and perineal pain, as well as bowel and sexual dysfunction. (In addition, in male pelvic pain patients, it’s common for them to feel as though they have a golf ball or tennis ball in their perineum.)

Despite the NIH’s edict, and more than 15 years later, men with pelvic pain are still getting that diagnosis to nowhere: “chronic nonbacterial prostatitis.”

Just ask Derrick.

A successful CFO, and an upbeat family man, Derrick is happily married with three children. It was in early 2002 that he began experiencing perineal pain, post-ejaculatory pain, and pain with sitting.

For nearly three years he was left to flounder in the misdiagnosis loop of chronic nonbacterial prostatitis. During that time, he endured several painful and misdirected tests and procedures at his urologist’s office. At one point, he even believed he had cancer.

“I was pretty frustrated and it was psychologically pretty challenging,” he says. “I was in my early 30s, but I felt very old. It impacted my sex life and all of my relationships.”

Because of the effect it was having on his life, Derrick sought help from a psychiatrist. It was his psychiatrist who referred him to a doctor in San Francisco who diagnosed him with pelvic pain and sent him to Liz for physical and occupational therapy.

“PT has been the only thing that has helped my pain and discomfort,” he says. “Now it’s something that I must manage through therapy every two to three months, but I’m okay with that.”

As both Tony and Derrick discovered, the right PT is the best treatment for men suffering with pelvic pain.

For the most part, there are four rungs to the ladder of pelvic pain treatment whether for a man or a woman. They are: working out external trigger points, working out internal trigger points and lengthening tight muscles, connective tissue manipulation, and correcting structural abnormalities.

For male patients, the internal trigger point release and muscle lengthening (internal work) is done via the anus because this is how the PT can gain access to the pelvic floor muscles. (Click here to read more about the right PT for pelvic pain.)

Despite the proven fact that PT is the best treatment for pelvic pain in men, it’s often difficult for men to get into the door of a pelvic pain PT clinic. That’s because not all pelvic floor PTs treat men. This is the second major reason men have an even harder time than women getting on the road to recovery from pelvic pain.

Today, the majority of pelvic floor PTs are women. And, many of these women are uncomfortable treating the opposite sex. For some female PTs, it simply boils down to them not being comfortable dealing with the penis and testicles. Among their qualms: What if the patient gets an erection? How do I deal with that?

Coming from a practice where 15% to 20% of our patients are men with pelvic pain, here’s our advice. If a male patient does get an erection, address it with a simple: “Don’t worry, it happens.” And move on. The bottom line is if you’re in the medical profession, you shouldn’t be intimidated by human anatomy. If you’re afraid to fly, don’t become a pilot. If you hate the water, don’t join the Navy. If you’re a vegan, don’t become a butcher. You get the picture!

Pelvic pain does not discriminate between sexes, and neither should those who treat it. Unfortunately even prominent organizations qualify pelvic pain as a “women’s health” issue. This needs to change.

To be fair, for some female PTs, their discomfort stems from the fact that they have received little to no formal education on how to treat the male pelvic floor. Frustratingly, there is very little education available to PTs on treating the pelvic floor in general. And what education is available is typically focused on the practical treatment of the female pelvic floor. For instance, when PTs take a class they practice on other PTs. So female PTs practice on other women, and when they return to their clinics, they’re not confident treating the male pelvic floor. While this is more understandable than simply not treating male patients because of a social discomfort, it’s still not acceptable.

The good news is that, in general, men are actually less complicated to treat than women. For one thing, there is no vestibule to deal with. The vestibule is an organ that’s full of nerves with the potential to become angry. In addition, the male pelvic floor doesn’t have mucosa that’s exposed to outside bacteria or other agents; therefore, men aren’t as vulnerable as women to UTIs and yeast infections, which can exacerbate the pain cycle. Lastly, male patients aren’t dealing with the large fluctuations in hormones that female patients deal with.

Conversely, what male patients and female patients do have in common is that with the male pelvic floor, as with the female pelvic floor, musculoskeletal impairments such as hypertonic muscles, connective tissue restrictions, pudendal nerve irritation, and myofascial trigger points commonly cause the symptoms of pelvic pain in men.

Another commonality is that lifestyle issues contribute to male pelvic pain just as they do to female pelvic pain. For instance, in Tony’s case, his activities that might have contributed to his pain included a history of doing upwards of 200 sit ups a day, and his regular long bike rides. Plus, at a young age he was told to “pucker” or hold his pelvic floor in order to avoid getting hemorrhoids.

As for Derrick, not only did he sit for long hours every day at a desk, he also had a long commute to and from work.

“In addition to solving my pain issues, PT helped me understand how my problems might have started to begin with, and it taught me to avoid certain potential triggers,” says Tony, who no longer rides a bike, does sit ups, or holds his pelvic floor. In addition, he has set up a standing work station to give him the option of not sitting at work.

For his part, Derrick has cut back on his sitting, and when he does have to sit, he takes frequent breaks to stand up and move around.

Both men are thankful they were put on the right path to pelvic floor PT, and both men have the same resounding advice for other men who are suffering from pelvic pain and are looking for relief. “Try pelvic pain PT!” they both advise. “PT saved my life,” adds Tony.

What Pelvic Pain!? : Click here to read a detailed account of how PT got Tony better.

Now we want to hear from you!

If you are a man with pelvic pain, please share your experiences with us.

All our very best,

Stephanie and Liz